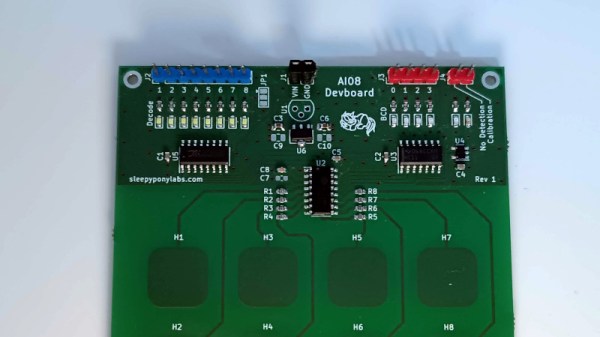

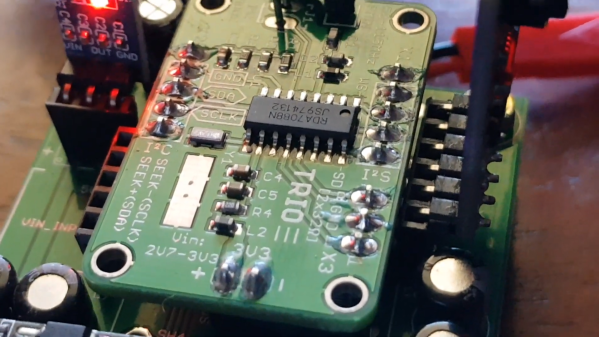

In the catalogue of the Chinese parts supplier LCSC can be found many parts not available from American or European suppliers, and thus anyone who wants to evaluate them can find themselves at a disadvantage. [Sleepy Pony Labs] had just such a part catch their eye, the Sam&Wing AI08 8 channel capacitive touch controller. How to evaluate a chip with little information? Design a dev board, of course!

The chip tested is part of a family all providing similar functionality, but with a variety of interface options. The part tested has eight touch inputs and a BCD output. Said output is used to feed a 74 series decoder chip and drive some LEDs. The touch pads were designed with reference to a Microchip application note which incidentally makes for fascinating reading on the subject as it covers far more than just simple touch buttons.

Whether or not you’ll need this touch chip is a matter for your own designs, however, what this project demonstrates is that with the ready availability of cheap custom PCBs and unexpected parts it’s not beyond reason to create boards just for evaluation purposes.

Perhaps the subject of a previous Hackaday piece would have found this board useful.

What if a socket on your phone or laptop fails? First off, it could be due to dust or debris. There’s swabs you can buy to clean a USB-C connector; perhaps adding some isopropyl alcohol or other cleaning-suitable liquids, you can get to a “good enough” state. You can also reflow pins on your connector, equipped with hot air or a sharp soldering iron tip, as well as some flux – when it comes to mechanical failures, this tends to remedy them, even for a short period of time.

What if a socket on your phone or laptop fails? First off, it could be due to dust or debris. There’s swabs you can buy to clean a USB-C connector; perhaps adding some isopropyl alcohol or other cleaning-suitable liquids, you can get to a “good enough” state. You can also reflow pins on your connector, equipped with hot air or a sharp soldering iron tip, as well as some flux – when it comes to mechanical failures, this tends to remedy them, even for a short period of time.