We’ve all made a few bad PCBs in our time. Sometimes they’re recoverable, and a few bodge wires will make ’em good. Sometimes they’re too far gone and we have to start again. But what if you could take an existing PCB, make a few mods, and turn it into the one you really want? That’s what “PCB Renewal” aims to do, as per the research paper from [Huaishu Peng] and the research group at the University of Maryland.

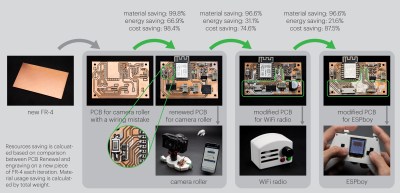

The concept is straightforward — PCB Renewal exists as a KiCad plugin that can analyze the differences between the PCB you have and the one you really want. Assuming they’re similar enough, it will generate toolpaths to modify the board with milling and epoxy deposition to create the traces you need out of the board you already have.

Obviously, there are limitations. You’ll never turn a PlayStation motherboard into something you could drop into an Xbox with a tool like this. Instead, it’s more about gradual modifications. Say you need to correct a couple of misplaced traces or missing grounds, or you want to swap one microcontroller for a similar unit on your existing board. Rather than making brand new PCBs, you could modify the ones you already have.

Of course, it’s worth noting that if you already have the hardware to do epoxy deposition and milling, you could probably just make new PCBs whenever you need them. However, PCB Renewal lets you save resources by not manufacturing new boards when you don’t have to.

We’ve seen work from [Huaishu Peng]’s research group before, too, in the form of an innovative “solderless PCB”.

Continue reading “PCB Renewal Aims To Make Old Boards Useful Again”