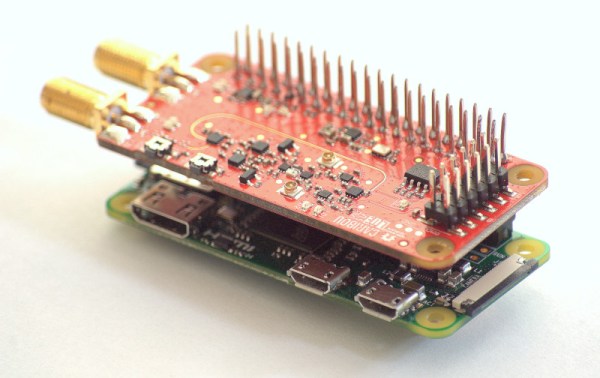

We don’t normally embrace the supernatural here at Hackaday, but when the topic turns to the radio frequency world, Arthur C. Clarke’s maxim about sufficiently advanced technology being akin to magic pretty much works for us. In the RF realm, the rules of electricity, at least the basic ones, don’t seem to apply, or if they do apply, it’s often with a, “Yeah, but…” caveat that’s sometimes hard to get one’s head around.

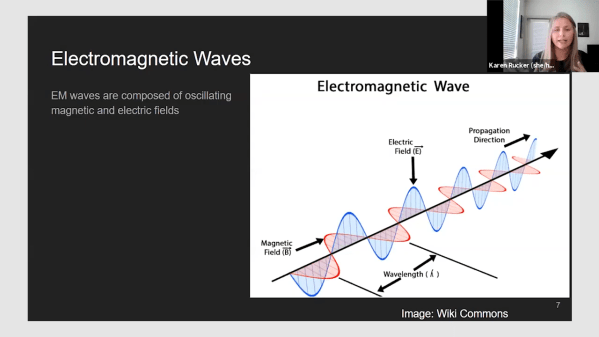

Perhaps nowhere does the RF world seem more magical than in antenna design. Sure, an antenna can be as simple as a straight piece or two of wire, but even in their simplest embodiments, antennas belie a complexity that can really be daunting to newbie and vet alike. That’s why we were happy to recently host Karen Rucker’s Introduction to Antenna Basics course as part of Hackaday U.

The class was held over a five-week period starting back in May, and we’ve just posted the edited videos for everyone to enjoy. The class is lead by Karen Rucker, an RF engineer specializing in antenna designs for spacecraft who clearly knows her business. I’ve watched the first video of the series and so far and really enjoy Karen’s style and the material she has chosen to highlight; just the bit about antenna polarization and why circular polarization makes sense for space communications was really useful. I’m keen to dig into the rest of the series playlist soon.

The 2021 session of Hackaday U may be wrapped up now, but fear not — there’s plenty of material available to look over and learn from. Head over to the course list on Hackaday.io, pick something that strikes your fancy, and let the learning begin!

Continue reading “New Video Series: Learning Antenna Basics With Karen Rucker”