Somehow, an Elka Synthex analog synthesizer made it onto [Mend it Mark]’s repair bench recently. It had a couple of dud buttons, and some keys produced the wrong tone. Remember, this is an analog synthesizer from the 1980s, so we’re talking basic 74LS chips and kin. Fortunately, Elka helped him with the complete repair manual, including schematics.

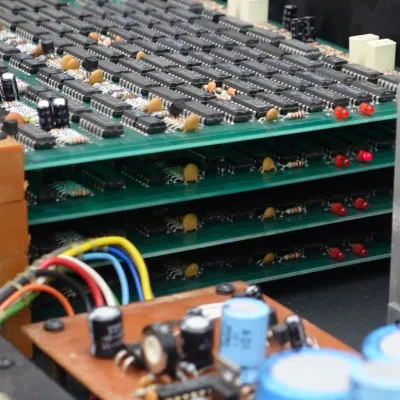

As usual, [Mark] starts by diagnosing the faults, using the schematics to mark the parts of the circuitry to focus on. Then, the synth’s bonnet is popped open to reveal its absolutely gobsmackingly delightful inner workings, with neatly modular PCBs attached to a central backplane. The entire unit is controlled by a 6502 MPU, with basic counter ICs handling tone generation, controlled by top panel settings.

The Elka Synthex is a polyphonic analog synthesizer produced from 1981 to 1985 and used by famous artists, including Jean-Michel Jarre. Due to its modular nature, [Mark] was quickly able to hunt down the few defective 74LS chips and replace them before testing the instrument by playing some synth tunes from Jean-Michel Jarre’s Oxygène album, as is proper with a 1980s synthesizer.

Looking for something simpler? Or, perhaps, you want something not quite that simple.

Continue reading “Repairing A Legendary Elka Synthex Analog Synthesizer”