There’s a wild new feature making repair jobs easier (not to mention less messy) and iFixit covers it in their roundup of the iPhone 16’s repairability: electrically-released adhesive.

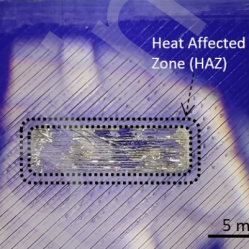

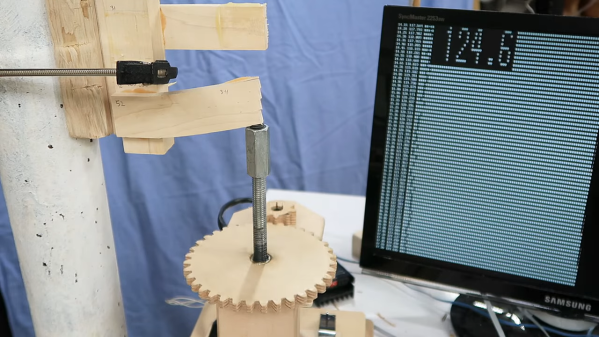

Here’s how it works. The adhesive looks like a curved strip with what appears to be a thin film of aluminum embedded into it. It’s applied much like any other adhesive strip: peel away the film, and press it between whatever two things it needs to stick. But to release it, that’s where the magic happens. One applies a voltage (a 9 V battery will do the job) between the aluminum frame of the phone and a special tab on the battery. In about a minute the battery will come away with no force, and residue-free.

There is one catch: make sure the polarity is correct! The adhesive releases because applying voltage oxidizes aluminum a small amount, causing Al3+ to migrate into the adhesive and debond it. One wants the adhesive debonded from the phone’s frame (negative) and left on the battery. Flipping the polarity will debond the adhesive the wrong way around, leaving the adhesive on the phone instead.

Some months ago we shared that Apple was likely going to go in this direction but it’s great to see some hands-on and see it in action. This adhesive does seem to match electrical debonding offered by a company called Tesa, and there’s a research paper describing it.

A video embedded below goes through the iPhone 16’s repairability innovations, but if you’d like to skip straight to the nifty new battery adhesive, that starts at the 2:36 mark.

Continue reading “Hands-on With New IPhone’s Electrically-Released Adhesive”