Of the machines from the 16-bit era, the Commodore Amiga arguably has the most active community decades later, and it’s a space which still has the power to surprise. Today we have a story which perhaps pushes the hardware farther than ever before: a demo challenge for the Amiga custom chips only, no CPU involved.

The Amiga was for a time around the end of the 1980s the most exciting multimedia platform, not because of the 68000 CPU it shared with other platforms, but because of its set of custom co-processors that handled tasks such as graphics manipulation, audio, and memory. Each one is a very powerful piece of silicon capable of many functions, but traditionally it would have been given its tasks by the CPU. The competition aims to find how possible it is to run an Amiga demo entirely on these chips, by using the CPU only for a loader application, with the custom chip programming coming entirely from a pre-configured memory map which forms the demo.

The demoscene is a part of our community known for pushing hardware to its limits, and we look forward to seeing just what they do with this one. If you have never been to a demo party before, you should, after all everyone should go to a demo party!

Amiga CD32 motherboard: Evan-Amos, Public domain.

![[Linus] playing his instrument](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/c64-queramin-feat.png?w=600&h=450)

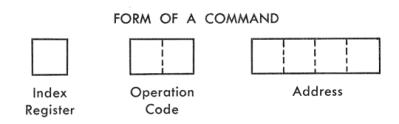

The G-15 can run several “high-level” programming languages, including Algol. The most popular, though, was Intercom. Intercom is an interactive programming language – you can type your program in right at the typewriter. It’s much closer to working with a basic interpreter than, say, a batch-processed IBM 1401 with punched cards. We’re still talking about the 1950s, though, so the language mechanics are quite a bit different from what we’re used to today.

The G-15 can run several “high-level” programming languages, including Algol. The most popular, though, was Intercom. Intercom is an interactive programming language – you can type your program in right at the typewriter. It’s much closer to working with a basic interpreter than, say, a batch-processed IBM 1401 with punched cards. We’re still talking about the 1950s, though, so the language mechanics are quite a bit different from what we’re used to today.