At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, Hackaday exists because people are out there building and documenting open source gadgets. If the person who built a particular gizmo is willing to show the world how they did it, consider us interested. Since you’re reading this, we’ll assume you are as well. Over the years, this mentality has been spreading out from the relatively niche hacker community into the greater engineering world, and we couldn’t be happier.

Case in point, the Poseidon project created at the California Institute of Technology. Developed by students [Sina Booeshaghi], [Eduardo Beltrame], and [Dylan Bannon], along with researcher [Jase Gehring] and professor [Lior Pachter], Poseidon consists of an open source digital microscope and syringe pump which can be used for microfluidics experiments. The system is not only much cheaper than commercial offerings, but is free from the draconian modification and usage restrictions that such hardware often comes with.

Case in point, the Poseidon project created at the California Institute of Technology. Developed by students [Sina Booeshaghi], [Eduardo Beltrame], and [Dylan Bannon], along with researcher [Jase Gehring] and professor [Lior Pachter], Poseidon consists of an open source digital microscope and syringe pump which can be used for microfluidics experiments. The system is not only much cheaper than commercial offerings, but is free from the draconian modification and usage restrictions that such hardware often comes with.

Of course, one could argue that major labs have sufficient funding to purchase this kind of gear without having to take the DIY route. That’s true enough, but what benefit is there to limiting such equipment to only the established institutions? As in any other field, making the tools available to a wider array of individuals (from professionals to hobbyists alike) can only serve to accelerate progress and move the state of the art forward.

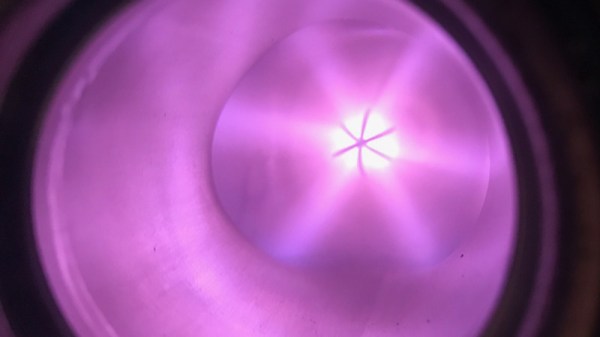

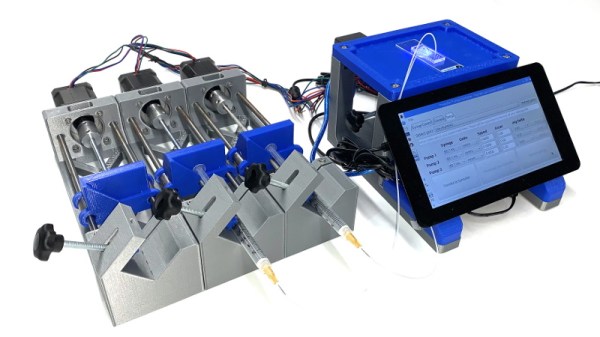

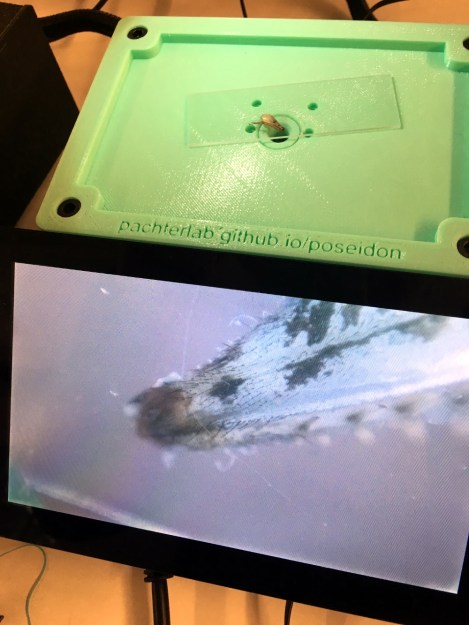

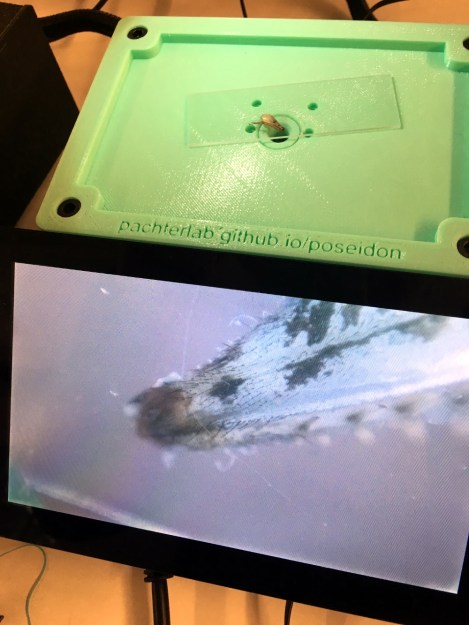

The Poseidon microscope consists of a Raspberry Pi, touch screen module, and commercially available digital microscope housed in a 3D printed stage. This device offers a large and clear view of the object under the microscope, and by itself makes an excellent educational tool. But when running the provided Python software, it doubles as a controller for the syringe pumps which make up the other half of the Poseidon system.

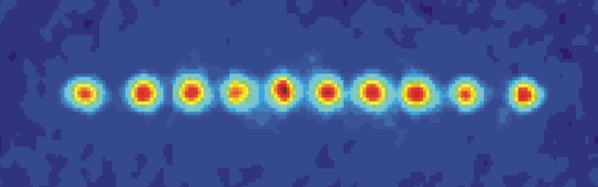

Almost entirely 3D printed, the pumps use commonly available components such as NEMA 17 stepper motors, linear bearings, and threaded rods to move the plunger on a syringe held in the integrated clamp. Controlled by an Arduino and CNC shield, these pumps are able to deliver extremely precise amounts of liquid which is critical for operations such as Single-cell RNA sequencing. All told a three pump system can be built for less than $400 USD, compared to the tens of thousands one might pay for commercially available alternatives.

The Poseidon project joins a relatively small, but very exciting, list of DIY biology projects that we’ve seen over the years. From the impressive open source CO2 incubator we saw a few years ago to the quick and dirty device for performing polymerase chain reaction experiments, there’s little doubt about it: biohacking is slowly becoming a reality.

Continue reading “Open Source Biological Gear For The Masses” →