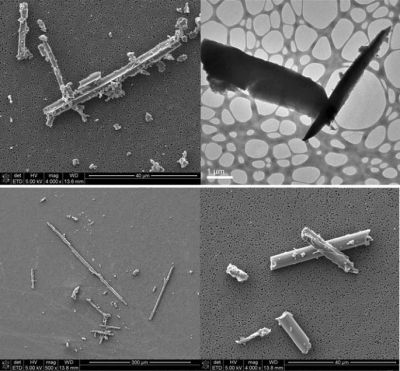

Could carbon fiber inflict the same kind of damage on the human body as asbestos? That’s the question which [Nathan] found himself struggling with after taking a look at carbon fiber-reinforced filament under a microscope, revealing a sight that brings to mind fibrous asbestos samples. Considering the absolutely horrifying impact that asbestos exposure can have, this is a totally pertinent question to ask. Fortunately, scientific studies have already been performed on this topic.

While [Nathan] demonstrated that the small lengths of carbon fiber (CF) contained in some FDM filaments love to get stuck in your skin and remain there even after washing one’s hands repeatedly, the aspect that makes asbestos such a hazard is that the mineral fibers are easily respirable due to their size. It is this property which allows asbestos fibers to nestle deep inside the lungs, where they pierce cell membranes and cause sustained inflammation, DNA damage and all too often lung cancer or worse.

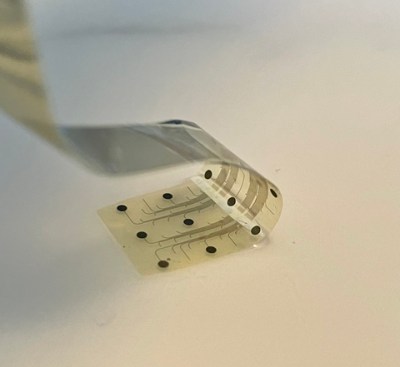

Clearly, the 0.5 to 1 mm sized CF strands in FDM filaments aren’t easily inhaled, but as described by [Jing Wang] and colleagues in a 2017 Journal of Nanobiotechnology paper, CF can easily shatter into smaller, sharper fragments through mechanical operations (cutting, sanding, etc.) which can be respirable. It is thus damaged carbon fiber, whether from CF reinforced thermal polymers or other CF-containing materials, that poses a potential health risk. This is not unlike asbestos — which when stable in-situ poses no risk, but can create respirable clouds of fibers when disturbed. When handling CF-containing materials, especially for processing, wearing an effective respirator (at least N95/P2) that is rated for filtering out asbestos fibers would thus seem to be a wise precaution.

The treacherous aspect of asbestos and kin is that diseases like lung cancer and mesothelioma are not immediately noticeable after exposure, but can take decades to develop. In the case of mesothelioma, this can be between 15 and 30 years after exposure, so protecting yourself today with a good respirator is the only way you can be relatively certain that you will not be cursing your overconfident young self by that time.