The Guinness brewery has a long history of innovation, but did you know that it was the birthplace of the t-test? A t-test is usually what underpins a declaration of results being “statistically significant”. Scientific American has a fascinating article all about how the Guinness brewery (and one experimental brewer in particular) brought it into being, with ramifications far beyond that of brewing better beer.

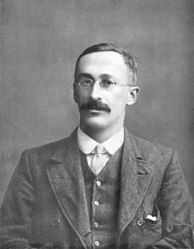

While the concept of statistical significance was not new at the time, Gosset’s significant contribution was finding a way to effectively and economically interpret data in the face of small sample sizes. That contribution was the t-test; a practical and logical approach to dealing with uncertainty.

As mentioned, t-testing had ramifications and applications far beyond that of brewing beer. The basic question of whether to consider one population of results significantly different from another population of results is one that underlies nearly all purposeful scientific inquiry. (If you’re unclear on how exactly the t-test is applied and how it is meaningful, the article in the first link walks through some excellent and practical examples.)

Dublin’s Guinness brewery has a rich heritage of innovation so maybe spare them a thought the next time you indulge in statistical inquiry, or in a modern “nitro brew” style beverage. But if you prefer to keep things ultra-classic, there’s always beer from 1574, Dublin castle-style.