This led [Doug] down the path of reverse-engineering and diagnosing the problem, ultimately throwing in the towel and downclocking the Altera CPLD inside the adapter after finding that it was running a smidge faster than the usual 6 MHz. This was accomplished initially by wiring in an external MCU as a crude (and inaccurate) clock source, but will be replaced with a 12 MHz oscillator later on. Exactly why the problem only exists on Linux and not on Windows will remain a mystery, with Waveshare support also being clueless.

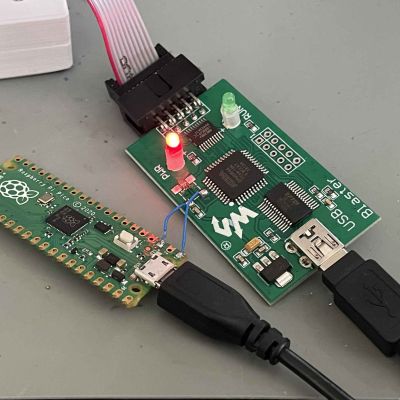

Undeterred, [Doug] then gambled on a $9 USB Blaster clone (pictured above), which turned out to be not only completely non-functional, but also caused an instant BSOD on Windows, presumably due to the faked FTDI USB functionality tripping up the Windows FTDI driver. This got fixed by flashing custom firmware by [Vladimir Duan] to the WCH CH552G-based board after some modifications shared in a project fork. This variety of clone adapters can have a range of MCUs inside, ranging from this WCH one to STM32 and PIC MCUs, with very similar labels on the case. While cracking one open we had lying around, we found a PIC18 inside, but if you end up with a CH552G-based one, this would appear to fully fix it. Which isn’t bad for the merest fraction of the official adapter.

Thanks to [mip] for the tip.