For the impatient Nissan owners who may be joining us from Google, a hacker by the name of [ea] has figured out how to get a root shell on the Bosch LCN2kai head unit of their 2015 Xterra, and it looks like the process should be the same for other vehicles in the Nissan family such as the Rogue, Sentra, Altima, and Frontier. If you want to play along at home, all you have to do is write the provided image to a USB flash drive and insert it.

Now for those of us who are a more interested in how this whole process works, [ea] was kind of enough to provide a very detailed account of how the exploit was discovered. Starting with getting a spare Linux-powered head unit out of a crashed Xterra to experiment with, the write-up takes the reader through each discovery and privilege escalation that ultimately leads to the development of a non-invasive hack that doesn’t require the user to pull their whole dashboard apart to run.

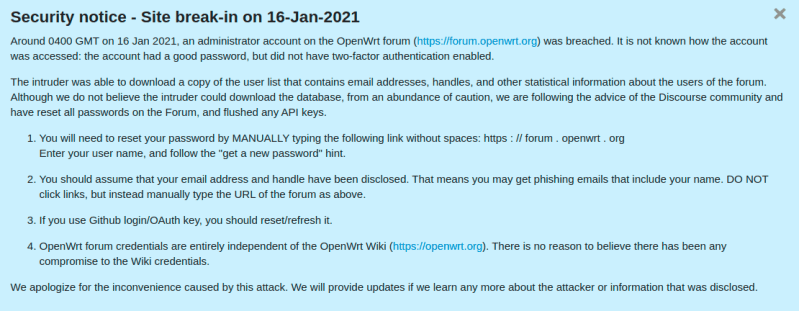

The early stages of the process will look familiar to anyone who’s messed with embedded Linux hacking. The first step was to locate the board’s serial port and connect it to the computer. From there, [ea] was able to change the kernel parameters in the bootloader to spawn an interactive shell. To make things a little easier, the boot scripts were then modified so the system would start up an SSH server accessible over a USB Ethernet adapter. With full access to the system, the search for exploits could begin.

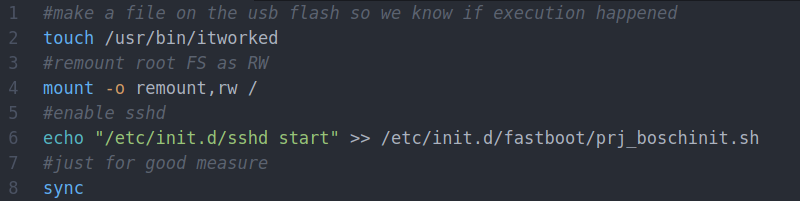

After some poking, [ea] discovered the script designed to mount USB storage devices had a potential flaw in it. The script was written in such a way that the filesystem label of the device would be used to create the mount point, but there were no checks in place to prevent a directory traversal attack. By crafting a label that read ../../usr/bin/ and placing a Bash script on the drive, it’s possible to run arbitrary commands on the head unit. The provided script permanently adds SSHd to the startup process, so when the system reboots, you’ll be able to log in and explore.

So what does [ea] want to do with this new-found exploit? It looks like the goal is to eventually come up with some custom programs that extend the functionality of the in-dash Linux system. As it seems like these “infotainment” systems are now an inescapable feature of modern automobiles, we’re certainly excited to see projects that aim to keep them under the consumer’s control.