Even though a computer’s memory map looks pretty smooth and very much byte-addressable at first glance, the same memory on a hardware level is a lot more bumpy. An essential term a developer may come across in this context is data alignment, which refers to how the hardware accesses the system’s random access memory (RAM). This and others are properties of the RAM and memory bus implementation of the system, with a variety of implications for software developers.

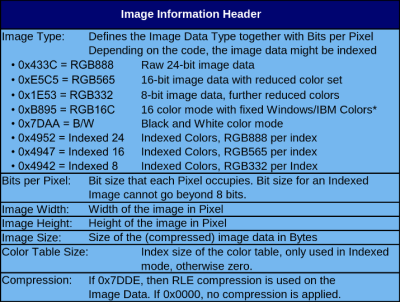

For a 32-bit memory bus, the optimal access type for some data would be a four bytes, aligned exactly on a four-byte border within memory. What happens when unaligned access is attempted – such as reading said four-byte value aligned halfway into a word – is implementation defined. Some hardware platforms have hardware support for unaligned access, others throw an exception that the operating system (OS) can catch and fallback to an unaligned routine in software. Other platforms will generally throw a bus error (SIGBUS in POSIX) if you attempt unaligned access.

Yet even if unaligned memory access is allowed, what is the true performance impact? Continue reading “Data Alignment Across Architectures: The Good, The Bad And The Ugly”