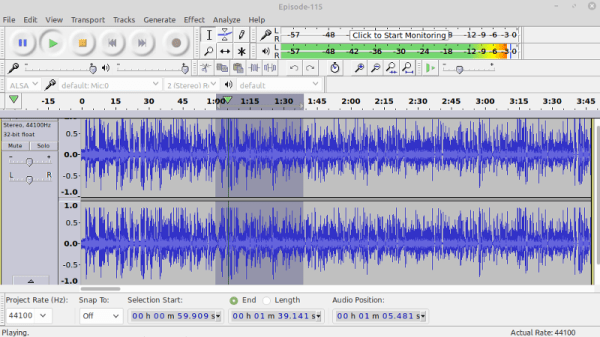

When we last checked in on the Audacity community, privacy-minded users of the free and open source audio editor were concerned over proposed plans to add telemetry reporting to the decades old open source audio editing software. More than 1,000 comments were left on the GitHub pull request that would have implemented this “phone home” capability, with many individuals arguing that the best course of action was to create a new fork of Audacity that removed any current or future tracking code that was implemented upstream.

For their part, the project’s new owners, Muse Group, argued that the ability for Audacity to report on the user’s software environment would allow them to track down some particularly tricky bugs. The tabulation of anonymous usage information, such as which audio filters are most commonly applied, would similarly be used to determine where development time and money would best be spent. New project leader Martin “Tantacrul” Keary personally stepped in to explain that the whole situation was simply a misunderstanding, and that Muse Group had no ill intent for the venerable program. They simply wanted to get a better idea of how the software was being used in the real-world, but after seeing how vocal the community was about the subject, the decision was made to hold off on any changes until a more broadly acceptable approach could be developed.

For their part, the project’s new owners, Muse Group, argued that the ability for Audacity to report on the user’s software environment would allow them to track down some particularly tricky bugs. The tabulation of anonymous usage information, such as which audio filters are most commonly applied, would similarly be used to determine where development time and money would best be spent. New project leader Martin “Tantacrul” Keary personally stepped in to explain that the whole situation was simply a misunderstanding, and that Muse Group had no ill intent for the venerable program. They simply wanted to get a better idea of how the software was being used in the real-world, but after seeing how vocal the community was about the subject, the decision was made to hold off on any changes until a more broadly acceptable approach could be developed.

Our last post on the subject ended on a high note, as it seemed like the situation was on the mend. While there was still a segment of the Audacity userbase that was skeptical about remote analytics being added into a program that never needed it before, representatives from the Muse Group seemed to be listening to the feedback they were receiving. Keary assured users that plans to implement telemetry had been dropped, and that should they be reintroduced in the future, it would be done with the appropriate transparency.

Unfortunately, things have only gotten worse in the intervening months. Not only is telemetry back on the menu for a program that’s never needed an Internet connection since its initial release in 2000, but this time it has brought with it a troubling Privacy Policy that details who can access the collected data. Worse, Muse Group has made it clear they intend to move Audacity away from its current GPLv2 license, even if it means muscling out long-time contributors who won’t agree to the switch. The company argues this will give them more flexibility to list the software with a wider array of package repositories, a claim that’s been met with great skepticism by those well versed in open source licensing.

Continue reading “Muse Group Continues Tone Deaf Handling Of Audacity”