When it comes to electronic design, breadboarding a circuit is the fun part — the creative juices flow, parts come and go, jumpers build into a tangled mess, but it’s all worth it when the circuit finally comes to life. Then comes the “What have I done?” phase, where you’ve got to backtrack through the circuit to document exactly how you built it. If only there was a better way.

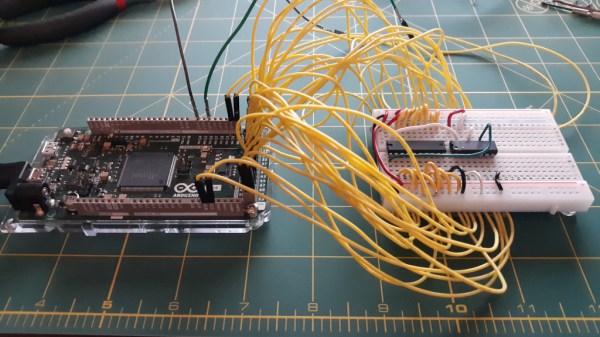

Thanks to [Nick Bild], there is, in the form of the “Schematic-o-matic”, which aims to automate the breadboard documentation process. The trick is using a breadboard where each bus bar is connected to an IO pin on an Arduino Due. A program runs through each point on the breadboard, running a continuity test to see if there’s a jumper connecting them. A Python program then uses the connection list, along with some basic information about where components are plugged into the board, to generate a KiCad schematic.

[Nick] admits the schematics are crude at this point, and that it’s a bit inconvenient to remove some components, like ICs, from the breadboard first to prevent false readings. But this seems like one of those things where getting 80% of the work done automatically and worrying about the rest later is a big win. Plus, we can see a path forward to automatic IC probing, and even measurement of passive components too. But even as it is, it’s a great tool.

Continue reading “Tricked-Out Breadboard Automatically Draws Schematics Of Whatever You Build” →