There is a technology that will allow you to add inks, resins, and paints to any flat surface. Screen printing has been around since forever, and although most of the tutorials and guides out there will tell you how to screen print onto t-shirts, [Ben Krasnow] had the idea of putting patterns of paint on acrylic, metal, or even ITO glass for electroluminescent displays. With screen printing, the devil is in the details, but lucky enough for all of us, [Ben] figured everything out and is sharing his knowledge with us.

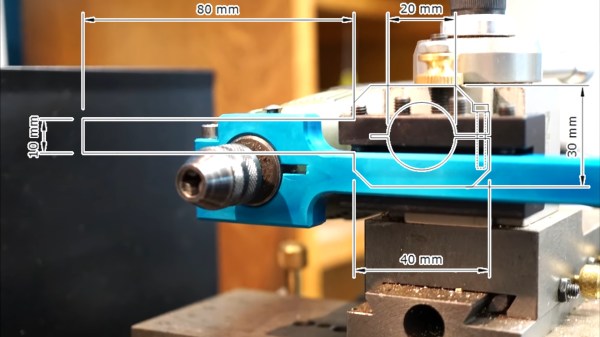

The ten thousand foot view of screen printing is simple enough — put some ink on a screen that has some photoemulsion, and squeegee it through onto a t-shirt. While this isn’t wrong, there’s a lot of technique, and things will go wrong if this is your first time doing it. Screens are easy, and the best way to get those is by buying a pre-stretched frame. The photoemulsion is a bit different. The old way of applying a photoemulsion is by squeegeeing it on with a bizarre tool. It’s almost impossible to get a thin consistent layer with this technique, so [Ben] recommends just buying some photoemulsion film.

Once the photoemulsion is on the screen and dry, you need to put an image on this. The photoemulsion cures hard with UV, so the traditional technique is using transparency (actually, the real old-school way is using a camera obscura…). Transparency sheets for laser printers work, but 30-lb vellum is actually more transparent to UV light than clear acetate sheets. This is then applied print side down to the dry screen, and believe me when I say this is the most important part. You will not get a good screen print if there is not direct contact between your photomask and your photoemulsion. This is so important, it may be worth considering some experiments in vinyl cutting to create the photomask.

With the screen developed, it’s simply a matter of globbing on some ink and pressing it onto a piece of acrylic. [Ben] used regular oil paints, an unmixed artists’ oil paint, and the professional solution, epoxy-based screenprinting paint. By far, the epoxy paint gave the best finish, but it’s a stinky mess that is nearly impossible to clean.

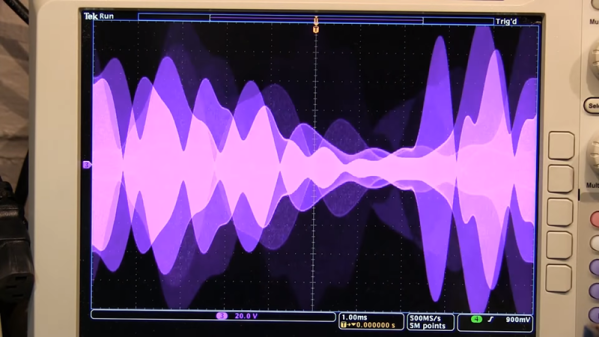

With a somewhat successful screenprinting setup, what will [Ben] be able to do? Well, he’s been working on electroluminescent displays, and the first EL displays were screenprinted anyway. More than that, you could use screen printing to create a resist for copper etching for creating your own PCBs. There’s a lot you can do when you can put epoxy down in a thin layer, like make a blockchain of Tide pods, and this is the best tutorial we’ve ever seen on using photoemulsions.

Continue reading “Adventures In Photopolymers With Ben Krasnow” →