Rejoice, those of us who have purchased a Nice-Power lab PSU from an Eastern source. Yes, the name might sound like a re-brand of a generic product, maybe you will even see this exact PSU on a shelf at a physical store near you, under a more local brand name and with a fair markup. Nevermind the circumstances, the most important part is that [Georgi Dobrishinov] found a way to add an ESP8266 to the PSU by tapping its internal UART control interface, and wrote a web UI for all your Internet-of-Lab-PSUs needs, called the PowerLinkESP project.

All you need is a Wemos D1 development board, or any other ESP8266 board that has UART pins exposed and handles 5 V input. [Georgi] brings everything else, from pictures showing you where to plug it in and where to tap 5 V, to extensive instructions on how to compile and upload the code, using just the Arduino IDE. Oh, and he tops it off with STLs for a 3D printed case, lest your Wemos D1 board flop around inside.

All you need is a Wemos D1 development board, or any other ESP8266 board that has UART pins exposed and handles 5 V input. [Georgi] brings everything else, from pictures showing you where to plug it in and where to tap 5 V, to extensive instructions on how to compile and upload the code, using just the Arduino IDE. Oh, and he tops it off with STLs for a 3D printed case, lest your Wemos D1 board flop around inside.

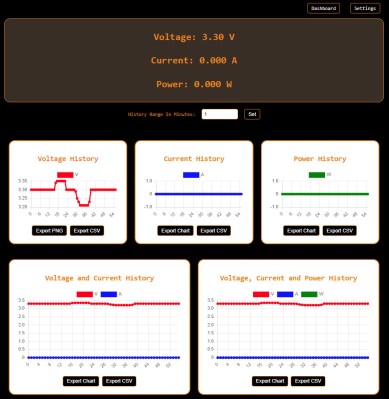

With [Georgi]’s software, you can monitor your PSU with interactive charts for all readings, export charts in both PNG and CSV, and access a good few features. Your ESP8266’s network uplink is also highly configurable, from an STA mode for a static lab config, to an AP mode for any on-the-go monitoring from your phone, and it even switches between them automatically! The firmware makes your PSU all that more practical, to the point that if you’re about to build an interface for your PSU, you should pay attention to [Georgi]’s work.

Lab PSUs with WiFi integration are worth looking into, just check out our review of this one; smart features are so nice to have, we hackers straight up rewrite PSU firmware to get there if we have to. Oh, and if you ever feel like standardizing your work so that it can interface to a whole world of measurement equipment, look no further than SCPI, something that’s easier to add to your project than you might expect, even with as little as Python and a Pi.