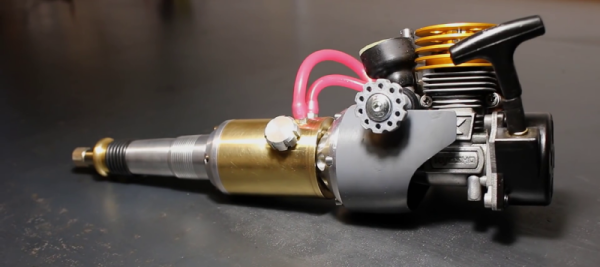

We really don’t know if the world needs it but we’re sure glad [johnnyq90] took the time to build one. We’re talking about a nitro powered rotary tool. Based on a Kyosho GX-12 nitro engine, commonly used in R/C cars, [johnnyq90] machines almost all other parts in his shop to make a really cool ‘Nitro-Dremel’. But success didn’t come at the first try.

The first prototype was made using a COX 049 engine but the lack of proper lubrication cause damage to the crankshaft. Because of this setback, [johnnyq90] swaps it out with a O.S Max 10 Aero engine he had lying around in the shop. That didn’t work out so well as the engine was quite hard to start. On the third try he finally decided to use the 2.1 cc Kyosho GX-12 engine to power up his 20.000 rpm tool. As noisy as one would expect and, from the videos it seems quite powerful too as it easily pierces through an aluminium block, cuts steel like a breeze, and breezes through other less demanding feats.

But [johnnyq90] is no stranger to nitro engines nor to Hackaday. In the past he built, among other things, a nitro powered cordless drill and showed impressive feats of machining in a micro version of a Tesla turbine. We wonder what’s next…. a nitro powered tattoo gun perhaps?

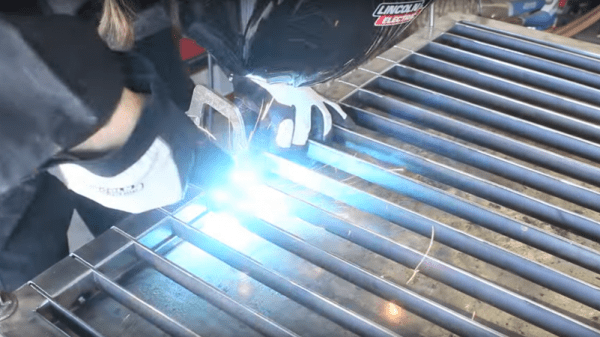

In the 20 minute video after the break, we enjoy watching the construction of the ‘Nitro-Dremel’, as well as other parts from two previously failed prototypes: