If you had a choice between going to your boss and asking for funds for a new piece of gear, would you rather ask for $3000 to buy off-the-shelf, or $200 for the parts to build the same thing yourself? Any self-respecting hacker knows the answer, and when presented with an opportunity to equip his lab with a new DIY syringe pump for $200, [Dr. D-Flo] rose to the challenge.

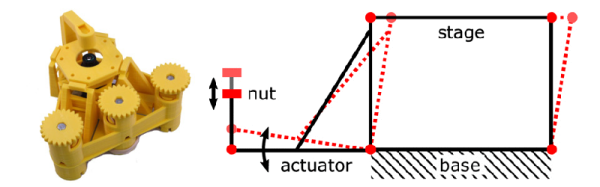

The first stop for [Dr. D-Flo] was, naturally, Hackaday.io, which is where he found [Naroom]’s syringe pump project. It was a good match for his budget and his specs, but he needed to modify some of the 3D printed parts a little to fit the larger syringes he intended to use. The base is aluminum extrusion, the drive train is a stepper motor spinning threaded rod and a captive nut in the plunger holders, and an Arduino and motor shield control everything. The drive train will obviously suffer from a fair amount of backlash, but this pump isn’t meant for precise dispensing so it shouldn’t matter. We’d worry a little more about the robustness of the printed parts over time and their compatibility with common lab solvents, but overall this was a great build that [Dr. D-Flo] intends to use in a 3D food printer. We look forward to seeing that one.

It’s getting so that that you can build almost anything for the lab these days, from peristaltic pumps to centrifuges. It has to be hard to concentrate on your science when there’s so much gear to make.

Continue reading “DIY Syringe Pump Saves Big Bucks For Hacker’s Lab”