Whether you’re making coffee or beer or complex chemicals, weighing your ingredients carefully and tracking them is key to getting good results. [Tech Dregs] decided to build a logging scale that would work seamlessly with his smartphone, and shared the design on YouTube.

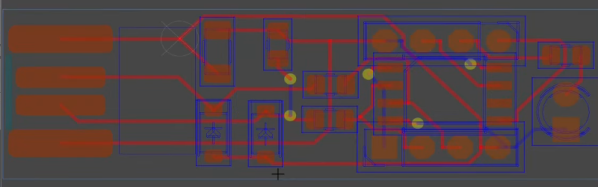

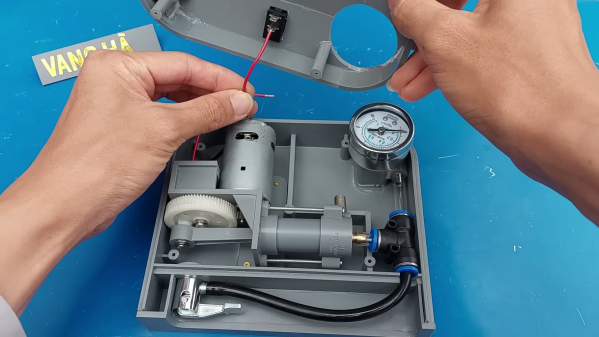

The design begins with a Greater Goods manual electronic scale, which was chosen for its convenient design and 750 gram load cell. Once cracked open, [Tech Dregs] pulled out the original PCB to replace it with his own. Only the original buttons are used, with an Seed Xiao ESP32-C3 replacing the scale’s original brains. The original LCD screen was swapped out for an OLED display, and it also got a rechargeable lithium battery for better usability.

The real value of the project, though, is its communication capability. It’s able to talk to an Android smartphone over Bluetooth Low Energy. Thanks to a custom app, [Tech Dregs] is able to log weight readings from the scale over time and even graph them live on the smartphone. As a demonstration, the scale is used to log the weight of a cup as it fills with a shot of coffee, which should serve [Tech Dregs] well in his coffee automation projects.

We’ve seen bathroom scales hacked before, too, with similar connectivity upgrades.

Continue reading “The BLE Datalogging Scale Of A Thousand Uses” →