The best hardware conference is just a few weeks away. This is the Hackaday Superconference, and it’s two days of talks, an extra day of festivities, soldering irons, and an epic hardware badge. We’ve been working on this badge for a while now, and it’s finally time to share some early details. This is an awesome badge and a great example of how to manufacture electronics on an extremely compressed timetable. This is badgelife, the hardware demoscene of electronic conference badges.

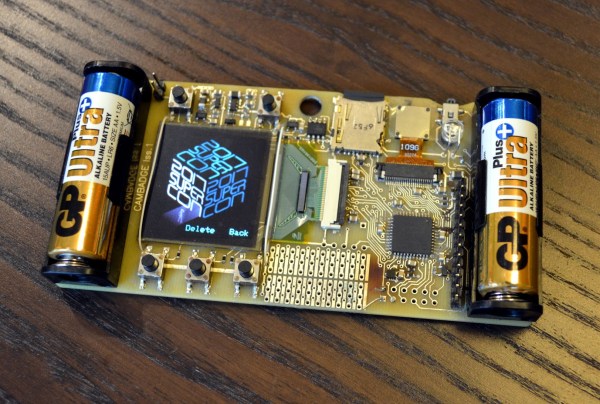

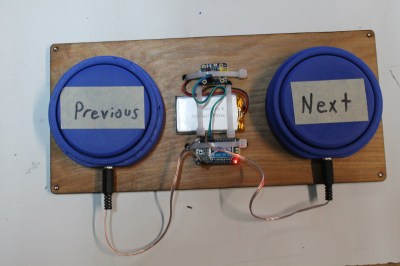

So, what does this badge do? It’s a camera. It has games, and it’s designed by [Mike Harrison] of Mike’s Electric Stuff. He designed and prototyped this badge in a single weekend. On board is a PIC32 microcontroller, an OV9650 camera module, and a bright, crisp 128×128 resolution color OLED display. Tie everything together with a few buttons, and you have a badge that’s really incredible.

So, how do you get one? You’ve got to come to the Hackaday Superconference. This year we’re doing things a bit differently and opening the doors a day early to get the hacker village started with badge hacking topped off by a party that evening and everyone coming to Supercon is invited! This is a badge full of games, puzzles, and video capture and isn’t something to miss. We have less than 30 tickets left so grab your ticket now and read on.

Continue reading “Building The Hackaday Superconference Badge”