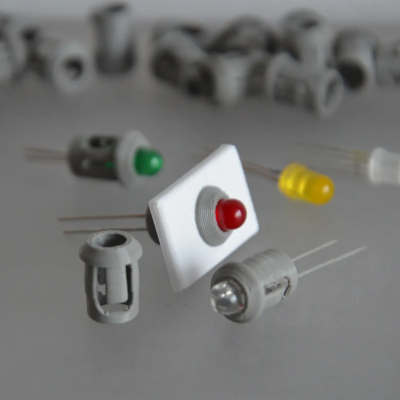

LED bezels (also known as LED panel-mount holders) are great, so how about 3D printing the next ones you need? Sure, they’re inexpensive to purchase and not exactly uncommon. But we all know that when working on a project, one doesn’t always have everything one might need right at hand. At times like that, 3D printing is like a superpower.

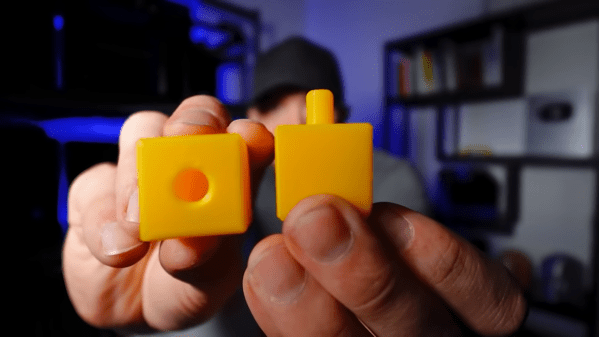

[firstgizmo]’s design is made with 3D printing in mind, and most printers should be able to handle making them. Need something a little different? You’re in luck because the STEP files are provided (something we love to see), which means modifications are just a matter of opening them in your favorite CAD program.

There’s not even any need to export to an STL after making tweaks, because STEP support in slicer programs is now quite common, ever since PrusaSlicer opened that door a few years ago.

Not using 5 mm LEDs, and need some other size? No problem, [firstgizmo] also has 3 mm, 8 mm, and 10 mm versions so that it’s easy to mount those LEDs on a panel. Combined with a tool that turns SVG files into multi-color 3D models, one can even make some panels complete with color and lettering to go with those LEDs. That might be just what’s needed to bring that midnight project to the next level.