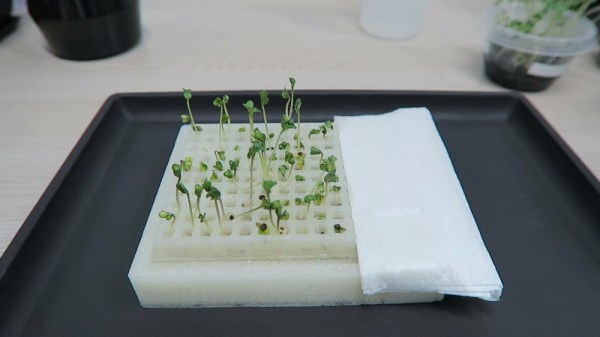

Microgreens, also known as vegetable confetti, are all the rage in fancy restaurants around the globe. Raised from a variety of different vegetable seeds, they’re harvested just past the sprout period, but before they would qualify as baby greens – usually 10-14 days after planting. There’s a variety of ways to grow microgreens, and [Mr Ben] has developed a 3D printed rig to help.

The rig consists of two parts – a seed tray and a water tray underneath. The seed tray consists of a grid to house the broccoli seeds to be grown, with small holes in each grid pocket to allow drainage. They’re sized just under the minimum seed size to avoid the seeds falling through, and also provide a path for root growth. Beneath the seed tray, the water tray provides the required hydration for plant growth, and helps train the roots downward.

[Mr Ben] notes there are some possible improvements to the design. He suggests PETG would be the ideal filament to use for the prints, as it is foodsafe unlike PLA and ABS. Additionally, precautions could be taken to better seal the water tray to avoid it becoming a breeding ground for insects.

Overall, it’s a tidy project that makes growing these otherwise delicate and expensive greens much neater and tidier. There’s also plenty of scope out there to automate plant care, too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Germinate Seeds With The Help Of 3D Printing” →