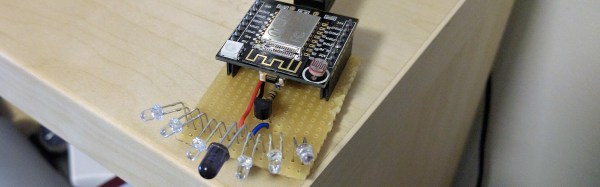

E-paper looks awesome, but it’s a pain to work with. You need only look at the homebrew implementations of e-paper drivers and the mess of SMD components for proof of that. [jarek] wanted to play around with e-paper and developed this tiny little driver for a Teensy. It’s a fun toy, and the simplest possible circuit necessary to drive this particular e-paper module.

I am once again asking if anyone knows where to buy this computer case. No, not a complete system – I just want the case, folding keyboard, and monitor integrated into an mATX enclosure.

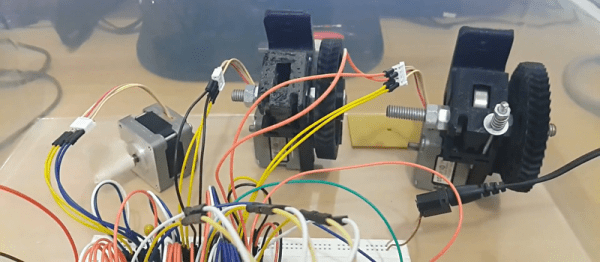

Back in 1985, a young [Matthias Wandel] built a remote control forklift out of a few windshield wiper motors, wood, and not much else. He’s rebuilt this toy recently, just to prove you can build anything with a stack of plywood and a wood gear template generator.

More Adafruit muppets they probably can’t call muppets. Yaaay. This time it’s J is for Joule. Watts that? A second.

The Raspberry Pi Project, one of our favorite projects in the Hackaday Prize that uses a Raspberry Pi, one of the most liked, viewed, and followed projects on Hackaday.io, and a technological tour de force the likes of which have not been seen since the invention of the steam engine got an update this week. [Arsenijs] and the rest of the Raspberry Pi Project team have released a version of their Raspberry Pi pinout helper. Previously, this tool was only used internally to the project, but since this pinout helper has such far-reaching utility they’ve decided to release a public version. Truly, they are kings among men.

This is possibly the coolest use of stacked plywood I’ve ever seen. It’s a spiral staircase, with each step made of 12 layers of plywood. The ‘spine’ of this staircase is a 3″ sch 40 steel pipe, with a proper foundation. The layer of ply are adhered to the pipe with construction adhesive, and each layer of ply is glued together with wood glue. No, it’s not up to code yet, but it was cheaper to build than just buying a spiral staircase.

[Brek] wrote a graphics library for the ubiquitous 128×64 monochromatic LCDs. It’s written for PICs, but damned if we can’t find a link to the library itself. Hopefully [Brek] will jump in the comments below.

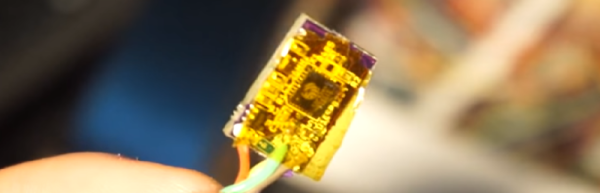

Those really, really cheap ESP8266 modules only have 512kB of Flash in them. Here’s how you upgrade those modules to 4MB. You can do it without a hot air gun, and all you need is a few cheap Flash chips.

Here’s a sound card for a Raspberry Pi. No, that’s not a completely dumb idea. This sound card uses quality op-amps, 24-bit ADCs and DACs, and has MIDI. If you’re experimenting with Pure Data or any other Linux audio toy, this could be a useful addition to your Pi stack.