We all have different ways of expressing excitement about new family members. [viscomjim] expressed his joy at the arrival of his first grandchild by building a twitter-enabled mirror/mood light. While we’d like to rage that this Internet of Things “thing” that people are doing has gone too far, this isn’t the first time we’ve seen this happen.

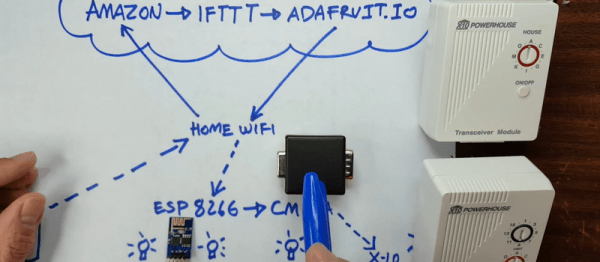

For the brains of his device [viscomjim] used an ESP8266 module. [Viscomjim] etched his grandchild’s name into the mirror and put some Neopixels behind it. When one of his family members tweets to the light’s channel they can change the color of the light to interact with their newest family member. We’re not so certain the Internet won’t find this and turn it into baby’s first 24 hour rave.

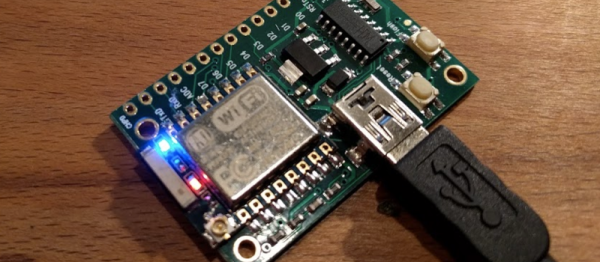

If you’d like to get in on the ESP8266 action, you’ll find the Huzzah board a good start, and we’ve got a special Hackaday edition in the store. Just sayin’.