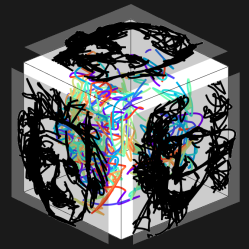

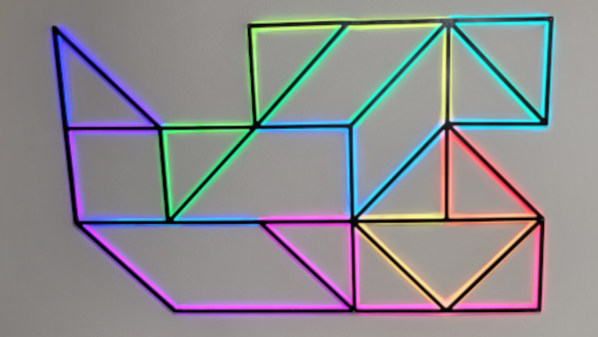

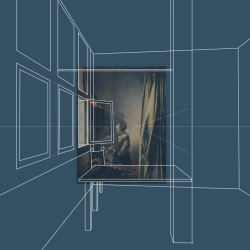

The process of creating something is always chock-full of things to learn, so it’s always a treat when someone takes the time and effort to share it. [Teadrinker] recently published the technique and workflow behind bringing art into VR, which explains exactly how they created a virtual reality art gallery that allows one to step inside paintings, called Art Plunge (free on Steam.)

It walks through not just how to obtain high-resolution images of paintings, but also discusses how to address things like adjusting the dynamic range and color grading to better match the intended VR experience. There is little that is objectively correct in technical terms when it comes to the aesthetic presentation details like brightness and lighting, so guidance on what does and doesn’t work well and how to tailor to the VR experience is useful information.

One thing that is also intriguing is the attention paid to creating a sense of awe for viewers. The quality, the presentation, and even choosing sounds are all important for creating something that not only creates a sense of awe, but does so in a way that preserves and cultivates a relationship between the art and the viewer that strives to stay true to the original. Giving a viewer a sense of presence, after all, can be more than just presenting stereoscopic 3D images or fancy lightfields.

You can get a brief overview of the process in a video below, but if you have the time, we really do recommend reading the whole breakdown.

Continue reading “Stepping Inside Art In VR, And The Workflow Behind It”