For the last few years or so, the story in the artificial intelligence that was accepted without question was that all of the big names in the field needed more compute, more resources, more energy, and more money to build better models. But simply throwing money and GPUs at these companies without question led to them getting complacent, and ripe to be upset by an underdog with fractions of the computing resources and funding. Perhaps that should have been more obvious from the start, since people have been building various machine learning algorithms on extremely limited computing platforms like this one built on the Atari 800 XL.

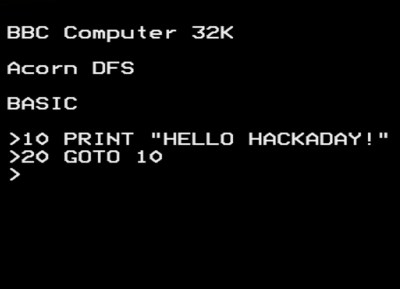

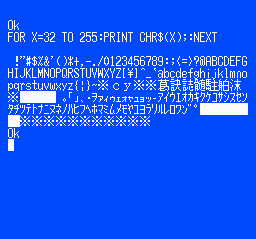

Unlike other models that use memory-intensive applications like gradient descent to train their neural networks, [Jean Michel Sellier] is using a genetic algorithm to work within the confines of the platform. Genetic algorithms evaluate potential solutions by evolving them over many generations and keeping the ones which work best each time. The changes made to the surviving generations before they are put through the next evolution can be made in many ways, but for a limited system like this a quick approach is to make small random changes. [Jean]’s program, written in BASIC, performs 32 generations of evolution to predict the points that will lie on a simple mathematical function.

While it is true that the BASIC program relies on stochastic methods to train, it does work and proves that it’s effective to create certain machine learning models using limited hardware, in this case an 8-bit Atari running BASIC. In previous projects he’s also been able to show how similar computers can be used for other complex mathematical tasks as well. Of course it’s true that an 8-bit machine like this won’t challenge OpenAI or Anthropic anytime soon, but looking for more efficient ways of running complex computation operations is always a more challenging and rewarding problem to solve than buying more computing resources.

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation. even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.