When you start an STM32 MCU with its default configuration, its CPU will tick along at a leisurely number of cycles on the order of 8 to 16 MHz, using the high-speed internal (HSI) clock source as a safe default to bootstrap from. After this phase, we are free to go wild with the system clock, as well as the various clock sources that are available beyond the HSI.

Increasing the system clock doesn’t just affect the CPU either, but also affects the MCU’s internal buses via its prescalers and with it the peripherals like timers on that bus. Hence it’s essential to understand the clock fabric of the target MCU. This article will focus on the general case of increasing the system clock on an STM32F103 MCU from the default to the maximum rated clock speed using the relevant registers, taking into account aspects like Flash wait states and the APB and AHB prescalers.

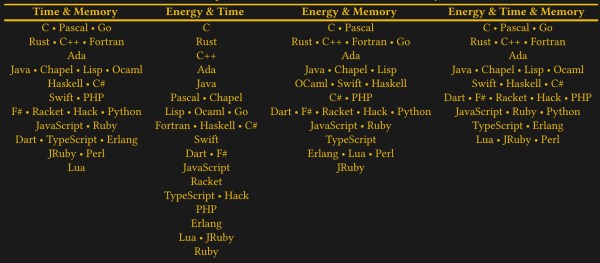

Although the Dhrystone benchmark is rather old-fashioned now, it’ll be used to demonstrate the difference that a faster CPU makes, as well as how complex accurately benchmarking is. Plus it’s just interesting to get an idea of how a lowly Cortex-M3 based MCU compares to a once top-of-the line Intel Pentium 90 CPU.

Continue reading “Bare Metal STM32: Increasing The System Clock And Running Dhrystone”