Although it might seem like there was a sudden step change from analog to digital sometime in the late 1900s, it was actually a slow, gradual change from things like record players to iPods or from magnetic tape to hard disk drives. Some of these changes happened slowly within the same piece of hardware, too. Take the Sony DXC-3000A, a broadcast camera from the 1980s. Although it outputs an analog signal, this actually has a discrete pixel CCD sensor capturing video. [Colby] decided to finish the digitization of this camera and converted it to output HDMI instead of the analog signal it was built for.

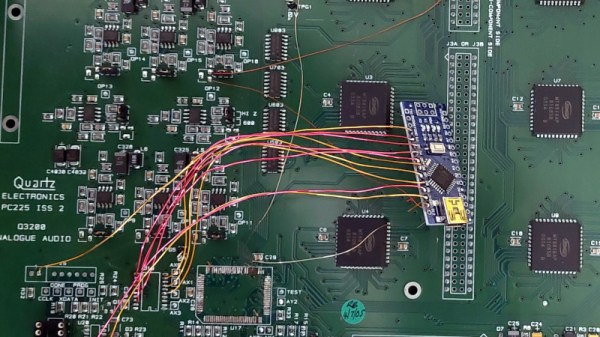

The analog signals it outputs are those that many of us are familiar with, though: composite video. This was an analog standard that only recently vanished from consumer electronics, and has a bit of a bad reputation that [Colby] thinks is mostly undeserved. But since so many semi-modern things had analog video outputs like these, inspiration was taken from a Wii mod chip that converts these consoles to HDMI. Unfortunately his first trials with one of these had confused colors, but it led him to a related chip which more easily outputted the correct colors. With a new PCB in hand with this chip, a Feather RP2040, and an HDMI port the camera is readily outputting digital video that any modern hardware can receive.

Besides being an interesting build, the project highlights a few other things. First of all, this Sony camera has a complete set of schematics, a manual meant for the end user, and almost complete user serviceability built in by design. In our modern world of planned obsolescence, religious devotion to proprietary software and hardware, and general user-unfriendliness this 1980s design is a breath of fresh air, and perhaps one of the reasons that so many people are converting old analog cameras to digital instead of buying modern equipment.