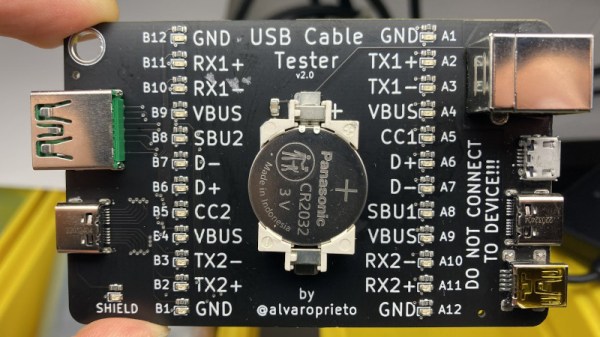

There’s no shame in admitting you’ve been burned by a cheapo USB cable — ever since some bean counter realized there was a few cents to be saved by producing “power only” USB cables, no hardware hacker has been safe. But with this simple tester from [Álvaro Prieto] in your arsenal, you’ll never be fooled again.

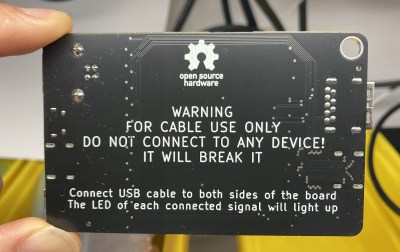

It’s about as straight-forward a design as possible, utilizing nothing more than a two dozen LEDs, their associated resistors, and a common CR2032 coin cell. Simply plugging both sides of your cable into the various flavors of USB connectors on the tester will complete the necessary circuits to light up the corresponding LEDs, instantly telling you how many intact wires are inside the cable. So whether you’re dealing with some shady cable that doesn’t have the full complement of conductors, or there’s some physical damage that’s severed a connection or two, you’ll know at a glance.

Obviously the tester is designed primarily for the 24 pins you’ll find in a proper USB-C connector, but it’s completely backwards compatible with older cables and connectors. We appreciate that he even included the chunky Type B connector, which we’ve always been fond of thanks to its robustness compared to the more common Mini and Micro variants.

Keep in mind though that this tester will only show you if there’s a connection between two pins, it won’t verify how much power it can actually handle. For that, you’ll need some extra equipment.