When it comes to PCs, Westerners are most most familiar with x86/x64 processors from Intel and AMD, with Apple Silicon taking up a significant market share, too. However, in China, a relatively new CPU architecture is on the rise. A fabless semiconductor company called Loongson has been producing chips with its LoongArch architecture since 2021. These chips remain rare outside China, but some in the West have been benchmarking them.

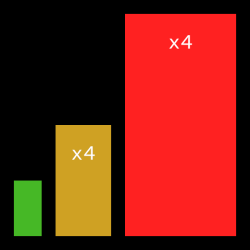

[Daniel Lemire] has recently blogged about the performance of the Loongson 3A6000, which debuted in late 2023. The chip was put through a range of simple benchmarking tests, involving float processing and string transcoding operations. [Daniel] compared it to the Intel Xeon Gold 6338 from 2021, noting the Intel chip pretty much performed better across the board. No surprise given its extra clock rate. Meanwhile, the gang over at [Chips and Cheese] ran even more exhaustive tests on the same chip last year. The Loongson was put through typical tasks like compressing archives and encoding video. The outlet came to the conclusion that the chip was a little weaker than older CPUs like AMD’s Zen 2 line and Intel’s 10th generation Core chips. It’s also limited as a four-core chip compared to modern Intel and AMD lines that often start at 6 cores as a minimum.

If you find yourself interested in Loongson’s product, don’t get too excited. They’re not exactly easy to lay your hands on outside of China, and even the company’s own website is difficult to access from beyond those shores. You might try reaching out to Loongson-oriented online communities if you seek such hardware.

Different CPU architectures have perhaps never been more relevant, particularly as we see the x86 stalwarts doing battle with the rise of desktop and laptop ARM processors. If you’ve found something interesting regarding another obscure kind of CPU, don’t hesitate to let the tipsline know!