There’s an adage coined by [Ian Betteridge] that any headline ending in a question mark can be answered by the word “No”. However, Lorentz invariance – the theory that the same rules of physics apply in the same way in all frames of reference, and an essential component of special relativity – has been questioned for some time by researchers trying to unify general relativity and quantum field theory into a theory of quantum gravity. Many theories of quantum gravity break Lorentz invariance by giving photons with different energy levels very slightly different speeds of light – a prediction which now looks less likely since researchers recently analyzed gamma ray data from pulsed astronomical sources, and found no evidence of speed variation (open-access paper).

The researchers specifically looked for the invariance violations predicted by the Standard-Model Extension (SME), an effective field theory that unifies special relativity with the Standard Model. The variations in light speed which it predicts are too small to measure directly, so instead, the researchers analyzed gamma ray flare data collected from pulsars, active galactic nuclei, and gamma-ray bursts (only sources that emitted gamma rays in simultaneous pulses could be used). Over such great distances as these photons had traveled, even slight differences in speed between photons with different energy levels should have added up to a detectable delay between photons, but none was found.

This work doesn’t disprove the SME, but it does place stricter bounds on the Lorentz invariance violations it allows, about one and a half orders of magnitude stricter than those previously found. This study also provides a method for new experimental data to be more easily integrated into the SME. Fair warning to anyone reading the paper: the authors call their work “straightforward,” from which we can only conclude that the word takes on a new meaning after a few years studying mathematics.

If you want to catch up on relativity and Lorentz invariance, check out this quick refresher, or this somewhat mind-bending explanation. For an amateur, it’s easier to prove general relativity than special relativity.

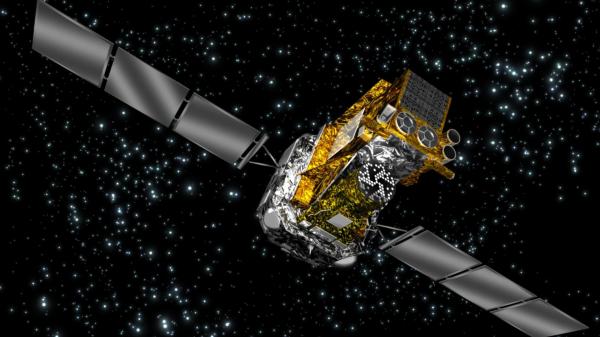

Top image: Crab Pulsar, one of the gamma ray sources analysed. (Credit: J. Hester et al., NASA/HST/ASU/J)

Some months back, CERN announced

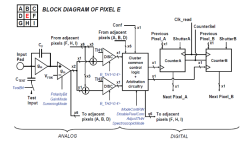

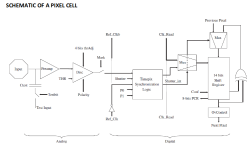

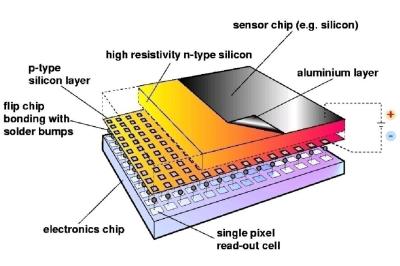

Some months back, CERN announced  The Analog front end consists of a pre-amplifier followed by a window discriminator which has upper and lower threshold levels. The discriminator has four bits for threshold adjustment as well as polarity sensing. This allows the capture window to be precisely set. The rest of the digital electronics – multiplexers, shift registers, shutter and logic control – helps extract the data.

The Analog front end consists of a pre-amplifier followed by a window discriminator which has upper and lower threshold levels. The discriminator has four bits for threshold adjustment as well as polarity sensing. This allows the capture window to be precisely set. The rest of the digital electronics – multiplexers, shift registers, shutter and logic control – helps extract the data.