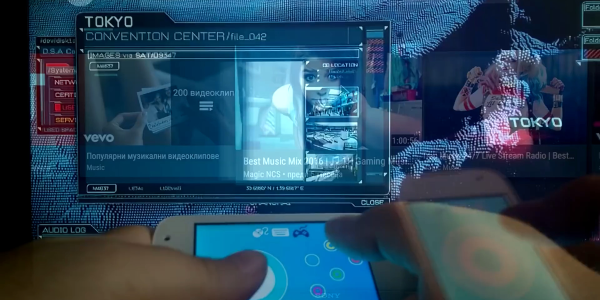

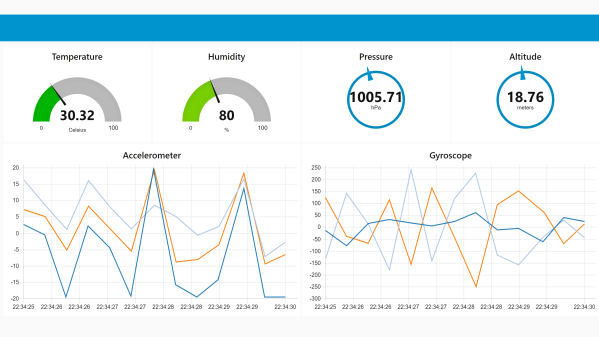

Some of us are suckers for new hardware. There’s absolutely nothing shameful about a drawer overflowing with gamepads, roll-up keyboards, and those funny-shaped ergonomic mice. MyTeleTouch won’t sate your itch for new hardware because [Dimitar Danailov] didn’t design hardware you hold, because it uses your phone as a catch-all Human Interface Device, HID. A dongle plugs into a standard USB port, and your Android phone can emulate a USB keyboard, mouse, or gamepad over Bluetooth.

Chances are high that you already set up your primary computer with your favorite hardware, but we think we’ve found a practical slant for a minimalist accessory. Remember the last time you booted an obsolete Windows desktop and dug out an old mouse with a questionable USB plug? How long have you poked around the bottom of a moving box trying to find a proprietary wireless keyboard dongle, when you just wanted to type a password on your smart TV? What about RetroPi and a game controller? MyTeleTouch isn’t going to transform your daily experience, but it’ll be there when you don’t want to carry a full-size keyboard down three flights of stairs to press {ENTER} on a machine that spontaneously forgot it has a touch screen. If you don’t have opportunities to play the hero very often, you can choose to play the villain. Hide this in a coworker’s USB port, and while they think you’re sending a text message, you could be fiddling with their cursor.

We enjoy a good prank that everyone can laugh off, and we love little keyboards and this one raises the (space) bar.