Whether you use your longboard as transportation or pleasure riding, night-time sessions can be harrowing if you’re screaming through poorly-lit places. The Beamboarder is a solution that is simple to build and easy to throw in a backpack whenever that giant ball of fire is above the horizon.

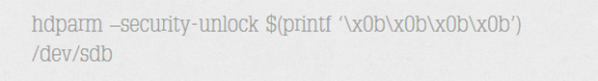

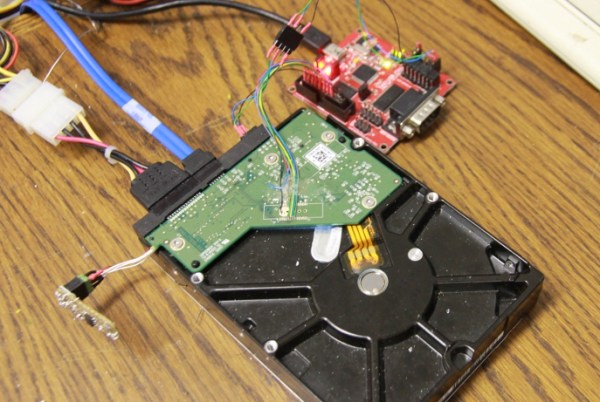

Boiled down it’s a high-power LED and a Lithium battery. How’s that for a hack? Actually it’s the “garbage” feel of it ([Lyon’s] words, not ours) that makes us smile. An old hard drive with as high of a capacity as possible was raided for parts. That sounded like a joke at first but the point is that early, large drives have bigger magnets inside. You need a really strong one because that’s all that will hold the LED to the front truck of our board. From there it’s a matter of attaching a CREE LED with thermal adhesive and wiring it up to the Lithium pack that has been covered in shrink tube to keep the elements out.

The headlight is under the board, which is courteous to oncoming traffic. Once you pull off this hack we’re sure you’ll want to go further so we suggest wheels with LED POV displays and there’s always the option of going full electric.