Sick of raiding old TVs and CRT monitors for flyback transformers to feed your high-voltage addiction? Never fear; if you’re careful, a 3D-printed flyback might be just the thing you’re looking for.

To be fair, it’s pretty easy to come by new flyback transformers, so building your own isn’t strictly necessary. But [SciTubeHD] was in the market for a particularly large flyback, in a good-natured effort to displace [Jay Bowles] from his lofty perch atop the flyback heap. And it’s also true that this project isn’t entirely 3D-printed, as the split core of the transformer was sourced commercially. The secondary coil, though, was where most of the effort went, with a secondary form made from multiple snap-together discs epoxied together for good measure. The secondary has about a kilometer of 30-gauge magnet wire while the primary holds just ten turns of 8-gauge wire covered with silicone high-voltage insulation.

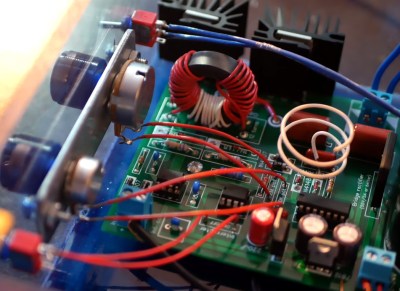

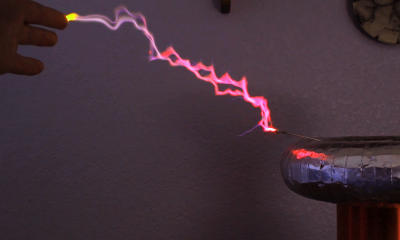

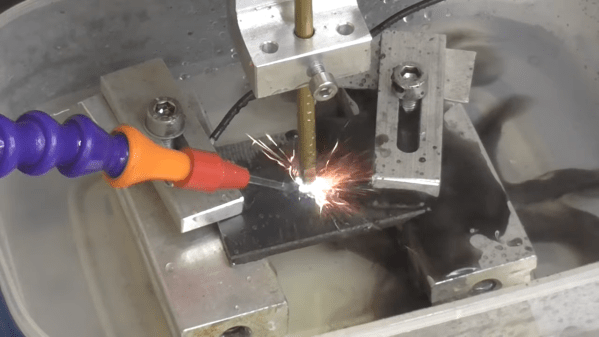

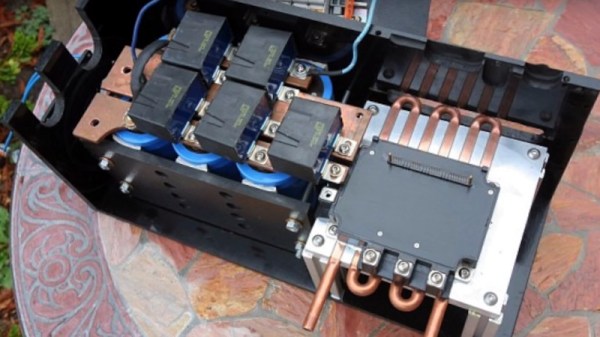

To decrease the likelihood of arcing, the transformer was placed in a plastic container filled with enough mineral oil liquid dielectric to cover the secondary. After degassing in a vacuum chamber for a day, [SciTubeHD] hooked the primary to a couple of different but equally formidable-looking full-bridge inverters for testing. The coil was capable of some pretty spicy arcs — [SciTubeHD] measured 20 amps draw at 35 volts AC input, so this thing isn’t to be trifled with. STL files for the core parts are coming up soon; we trust schematics for the power supply will be available, too.

Continue reading “Satisfy Your High-Voltage Urges With This Printable Flyback Transformer”