MDF is the cheapest and flattest wood you can buy at local hardware stores. It’s uniform in thickness, and easy to work with. It’s no wonder that it shows up in a lot of projects. MDF stands for Medium Density Fiberboard. It’s made by pressing materials together along with some steam, typically wood, fibers and glue. This bonds the fibers very tightly. Sometimes MDF is constructed much like plywood. Thinner layers of MDF will be made. Then those layers will be laminated together under glue and steam.The laminated MDF is not as good as the monolithic kind. It tends to tear and break out along the layers, but it’s hard to tell which kind you will get.

MDF is great, but it has a few properties to watch for. First, MDF is very weak in bending and tension. It has a Modulus of Elasticity that’s about half of plywood. Due to its structure, short interlocking fibers bound together by glue and pressure, it doesn’t take a lot to cause a crack, and then, quickly, a break. If you’d like to test this, take a sheet of MDF, cut it with a knife, flip it over, and hit the sheet right behind your cut. Chances are the MDF will split surprisingly easily right at that point.

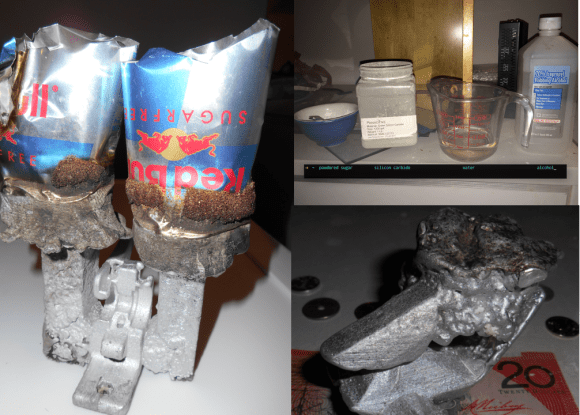

Because of the way MDF is constructed, fasteners tend to pull out of it easily. This means that you must always make sure a fastener that sees dynamic loads (say a bearing mount) goes through the MDF to the other side into a washer and bolt. MDF also tends to compress locally after a time, so even with a washer and bolt it is possible that you will see some ovaling of the holes. If you’re going to use screws, make sure they don’t experience a lot of force, also choose ones with very large threads instead of a finer pitch. Lastly, always use a pilot hole in MDF. Any particle board can split in alarming ways. For example, if you just drive a screw into MDF, it may appear to go well at first. Then it will suddenly jump back against you. This happened because the screw is compressing the fibers in front of it, causing an upward force. The only thing pressing against that force is the top layer of laminate contacting the threads. The screw then jumps out, tearing the top layer of particle board apart.

Continue reading “Materials To Know: Medium Density Fiberboard”