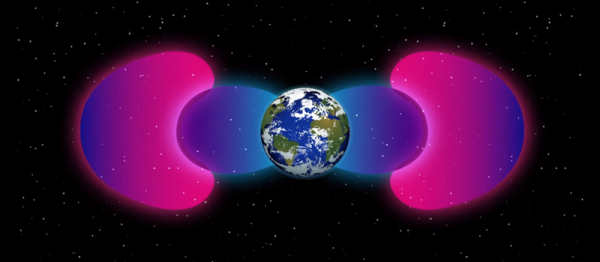

NASA spends a lot of time researching the Earth and its surrounding space environment. One particular feature of interest are the Van Allen belts, so much so that NASA built special probes to study them! They’ve now discovered a protective bubble they believe has been generated by human transmissions in the VLF range.

VLF transmissions cover the 3-30 kHz range, and thus bandwidth is highly limited. VLF hardware is primarily used to communicate with submarines, often to remind them that, yes, everything is still fine and there’s no need to launch the nukes yet. It’s also used for navigation and broadcasting time signals.

It seems that this human transmission has created a barrier of sorts in the atmosphere that protects it against radiation from space. Interestingly, the outward edge of this “VLF Bubble” seems to correspond very closely with the innermost edge of the Van Allen belts caused by Earth’s magnetic field. What’s more, the inner limit of the Van Allan belts now appears to be much farther away from the Earth’s surface than it was in the 1960s, which suggests that man-made VLF transmissions could be responsible for pushing the boundary outwards.

Continue reading “Humans May Have Accidentally Created A Radiation Shield Around Earth”

PUFFER — which stands for Pop-Up Flat-Folding Explorer Robot — is able to sense objects and adjust its profile accordingly by ‘folding’ itself into a smaller size to fit itself into nooks and crannies. It was designed so multiple PUFFERs could reside inside a larger craft and then be deployed to scout otherwise inaccessible terrain. Caves, lava tubes and shaded rock overhangs that could shelter organic material are prime candidates for exploration. The groups of PUFFERs will send the collected info back to the mother ship to be relayed to mother Earth.

PUFFER — which stands for Pop-Up Flat-Folding Explorer Robot — is able to sense objects and adjust its profile accordingly by ‘folding’ itself into a smaller size to fit itself into nooks and crannies. It was designed so multiple PUFFERs could reside inside a larger craft and then be deployed to scout otherwise inaccessible terrain. Caves, lava tubes and shaded rock overhangs that could shelter organic material are prime candidates for exploration. The groups of PUFFERs will send the collected info back to the mother ship to be relayed to mother Earth.