We’ve all been there — a steamy night in the rainforest of Papua New Guinea, sweaty slumber disturbed by the unmistakable sounds of gnawing. In the morning we discover that a rodent of unusual tastes has chewed the microphone cable of our transceiver right half in two, leaving us out of touch with base camp. If we had a nickel for every time that’s happened.

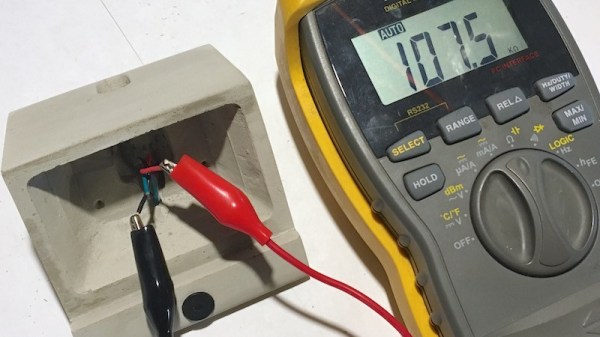

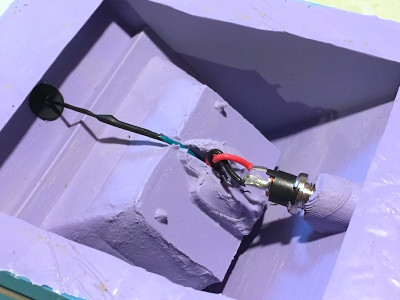

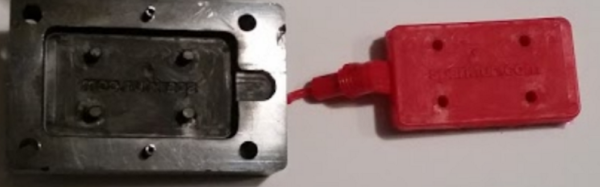

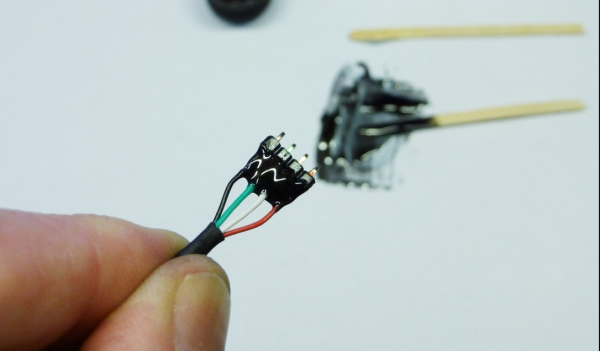

It may sound improbable, but that’s the backstory behind [Marius Taciuc]’s 3D-printed mic cord repair. Even with more mundane failure modes, the retractile cords on microphones are notoriously difficult to fix. Pretty much any of the usual suspects, like heat-shrink tubing or electrical tape, are going to do very little to restore the mechanical stability lost once that tough outer jacket is breached. [Marius]’s solution was to print as small an enclosure as possible to mechanically support the splice. The fit is tight, but there was just enough room to solder the wires and stuff everything back in place. Cable ties provide strain relief where the cord exits the splice, and a liberal squirt of hot glue pots the joint. It’s not perfect — we’ll bet the splice acts as a catch point and gets a little annoying after a while — but if it gets you back on the air fast and cheap, it probably makes sense.

[Marius] entered this rat-race beating hack into the Repairs You Can Print contest. Do you have an epic repair that was made possible by a 3D printer? Let the world know about it and you might just win a prize.

Continue reading “Repairs You Can Print: Fixing A Rat-Attacked Mic Cord”