If you have been a regular traveler on one of the world’s mass transit systems over the last few decades, you will have witnessed something of a technological revolution. Not necessarily in the trains themselves, though they have certainly changed, but in the signalling and system automation. Nineteenth and twentieth century human and electromechanical systems have been replaced by up-to-date computers, and in some cases the trains even operate autonomously without a driver. The position of every train is known exactly at all times, and with far less possibility for human error, the networks are both safer and more efficient.

As you might expect, the city-state of Singapore has a metro with every technological advance possible, recently built and with new equipment. It was thus rather unfortunate for the Singaporean metro operators that trains on their Circle Line started to experience disruption. Without warning, trains would lose their electronic signalling, and their safety systems would then apply the brakes and bring them to a halt. Engineers had laid the blame on electrical interference, but despite their best efforts no culprit could be found.

Eventually the problem found its way to the Singaporean government’s data team, and their story of how they identified the source of the interference makes for a fascinating read. It’s a minor departure from Hackaday’s usual hardware and open source fare, but there is still plenty to be learned from their techniques.

They started with the raw train incident data, and working in a Jupyter notebook imported, cleaned, and consolidated it before producing analyses for time, location, and train IDs. None of these graphs showed any pointers, as the incidents happened regardless of location, time, or train.

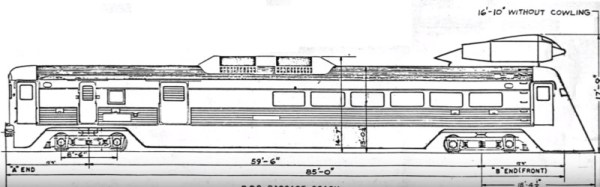

They then plotted each train on a Marey chart, a graph in which the vertical axis represents time and the horizontal axis represents stations along a line (Incidentally Étienne-Jules Marey’s Wikipedia entry is a fascinating read in itself). Since it represents the positions of multiple trains simultaneously they were able to see that the incidents happened when two trains were passing, hence their lack of correlation with location or time. The prospect of a rogue train as the source of the interference was raised, and analyzing video recordings from metro stations to spot the passing train’s number they were able to identify the unit in question. We hope that the repairs included a look at the susceptibility of the signalling system to interference as well as the faulty parts on one train.

We’ve been known to cover a few stories here with a railway flavor over the years. Mostly though they’ve been older ones, such as this film of a steam locomotive’s construction, or this tale of narrow gauge preservation.

[via Hacker News]

[Main image source: Singapore MRT Circle line trains image: 9V-SKA [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons]

![The front of the Soviet jet train on a monument in Tver, Russia. By Eskimozzz [PD], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/576px-d181d182d0b5d0bbd0b0.jpg?w=300)

!["Lawnmower" Locomotive in 1952 [Source: talyllyn.co.uk]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/jbs-1-2kw.jpg?w=400)