[Brett] is working on a video installation, and for the past few months, has been trying to get his hands on tiny CRTs any way he can. After initially coming up short, he happened across a karaoke machine from 2005, and got down to work.

Karaoke machines of this vintage are typically fairly low-rent affairs, built cheaply on simple PCBs. [Brett] found that the unit in question was easy to disassemble, having various modules on separate PCBs joined together with ribbon cables and headers. However, such machines rarely have video inputs, as they’re really only designed to display low-res graphics from CD-G format discs.

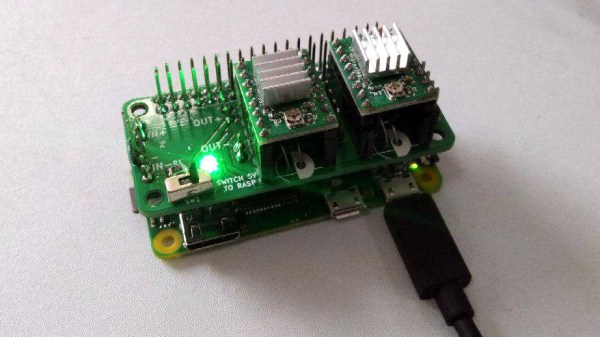

While investigating the machine, initial research online proved fruitless. In the end, a close look at the board revealed just what [Brett] was looking for – a pin labeled video in! After throwing in a Raspberry Pi Zero and soldering up the composite output to the karaoke machine’s input pin, the screen sprung to life first time! This initial success was followed by installing a Raspberry Pi 3 for more grunt, combined with a Screenly install – and a TRS adapter the likes of which we’ve never seen before. This allows video to be easily pushed to the device remotely over WiFi. [Brett] promises us there is more to come.

Karaoke is a sparse topic in the Hackaday archives, but we’ve seen a couple builds, like this vocal processor. If you’ve got the hacks, though? You know where to send ’em.