[MacGyver] would be proud of [Hyperspace Pirate]’s rough and ready method of producing acetylene gas from seashells and driftwood.

Acetylene, made by decomposing calcium carbide with water, is a vitally important industrial gas. Not only as a precursor in many chemical processes, but also as the fuel for the famous “blue wrench,” a tool without which auto mechanics working in the Rust Belt would be reduced to tears. To avoid this, [Hyperspace Pirate] started by beachcombing for the raw materials: shells to make calcium oxide and wood to make charcoal. Charcoal is pretty easy; you just cook chunks of wood in a reducing environment to drive off everything but the carbon. Making calcium oxide from the calcium carbonate in the shells isn’t much harder, with ground seashells heated in a propane-fired furnace to release carbon dioxide.

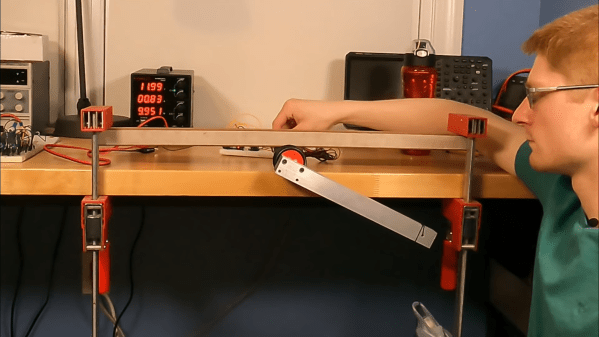

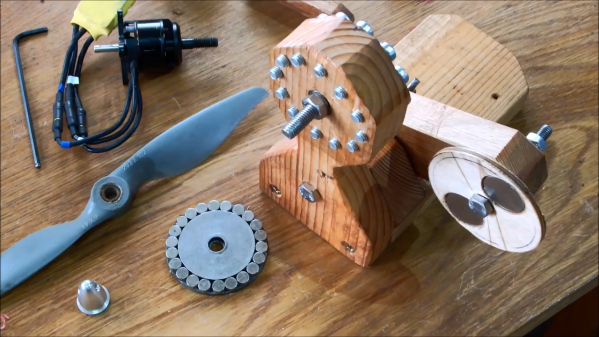

With the raw ingredients in hand, things get a little tricky. Making calcium carbide requires a lot of heat, far more than a simple propane burner can provide. [Hyperspace Pirate] decided to go with an electric arc furnace, to which end he cannibalized a 120 V to 240 V step-up converter for its toroidal transformer, which with a few extra windings provided the needed current to run an arc through carbon electrodes. This generated the needed heat, and then some, as the ceramic firebrick he was using to contain the inferno melted. After rewinding the melted secondary windings on his makeshift transformer and switching to a stainless steel crucible, he was able to make enough calcium carbide to generate an impressive amount of acetylene. The video below documents the process and the sooty results, as well as details a little of the excitement that metal acetylides offer.

For more about acetylene and its many uses, [This Old Tony] has you covered.

Continue reading “Desert Island Acetylene From Seashells And Driftwood”