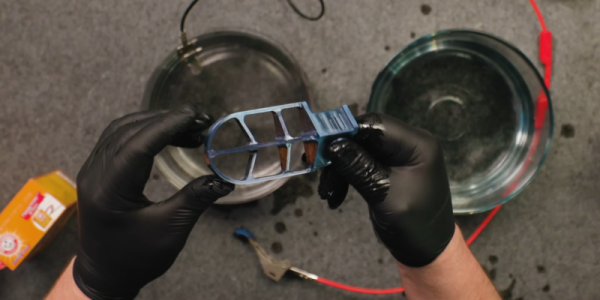

A multitool that weighs less than a penny? Yes, it exists. This video by [ToolTechGeek] shows his titanium flat-cut design tipping the scales at only 1.9 grams—lighter than the 2.5-gram copper penny jingling in your pocket. His reasoning: where most everyday carry (EDC) tools are bulky, overpriced, or simply too much, this hack flips the equation: reduce it to the absolute minimum, yet keep it useful.

You might have seen this before. This second attempt is done by laser-cutting titanium instead of stainless steel. Thinner, tougher, and rust-proof, titanium slashes the weight dramatically, while still keeping edges functional without sharpening. Despite the size, this tool manages to pack in a Phillips and flathead screwdriver, a makeshift saw, a paint-lid opener, a wire bender (yes, tested on a paperclip), and even a 1/4″ wrench doubling as a bit driver. High-torque screwdriving by using the long edges is a clever exploit, and yes—it scrapes wood, snaps zip ties, and even forces a bottle cap open, albeit a bit roughly.

It’s not about replacing your Leatherman; it’s about carrying something instead of nothing. Ultra-minimalist, featherlight, pocket-slip friendly—bet you can’t find a reason not to just have it in your pocket.

Continue reading “This Pocket Multitool Weighs Less Than A Penny”