There’s just something amazing about counting down and watching a rocket lift off the pad, soaring high into the sky. The excitement is multiplied when the rocket is one you built yourself. Amateur rocketry has been inspiring hackers and engineers for centuries. In the USA, modern amateur rocketry gained popularity after Sputnik-1, continuing on through the space race. Much of this history captured in the book Rocket Boys by Homer Hickam, which is well worth a read. This week’s Hacklet is dedicated to some of the best rocketry projects on Hackaday.io!

We start with [Sagar] and Guided Rocket. [Sagar] is building a rocket with a self stabilization system. Many projects use articulated fins for this, and [Sagar] plans to add fins in the future, but he’s starting with an articulated rocket motor. The motor sits inside a gimbal, which allows it to tilt about 10 degrees in any direction. An Arduino is the brain of the system. The Arduino gathers data from a MPU6050 IMU sensor, then determines how to steer the rocket motor. Steering is accomplished with a couple of micro servos connected to the gimbal.

We start with [Sagar] and Guided Rocket. [Sagar] is building a rocket with a self stabilization system. Many projects use articulated fins for this, and [Sagar] plans to add fins in the future, but he’s starting with an articulated rocket motor. The motor sits inside a gimbal, which allows it to tilt about 10 degrees in any direction. An Arduino is the brain of the system. The Arduino gathers data from a MPU6050 IMU sensor, then determines how to steer the rocket motor. Steering is accomplished with a couple of micro servos connected to the gimbal.

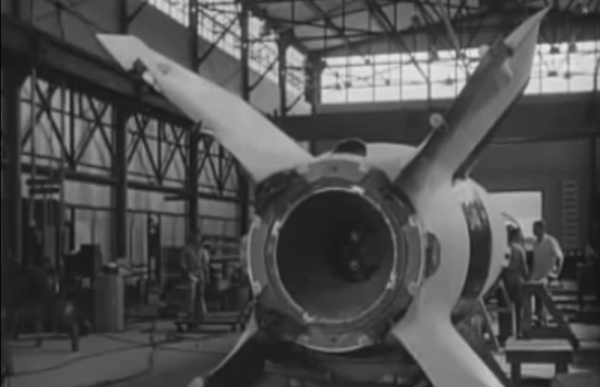

Next up is [Howie], with Homemade rocket engine. [Howie] is cooking some seriously hot stuff on his stove. Rocket candy to be precise, similar to the fuel [Homer Hickam] wrote about in Rocket Boys. This solid fuel is so named because one of the main ingredients is sugar. The other main ingredient is stump remover, or potassium nitrate. Everything is mixed and heated together on a skillet for about 30 minutes, then pushed into rocket engine tubes. It goes without saying that you shouldn’t try this one at home unless you’re really sure of what you’re doing!

Next up is [Howie], with Homemade rocket engine. [Howie] is cooking some seriously hot stuff on his stove. Rocket candy to be precise, similar to the fuel [Homer Hickam] wrote about in Rocket Boys. This solid fuel is so named because one of the main ingredients is sugar. The other main ingredient is stump remover, or potassium nitrate. Everything is mixed and heated together on a skillet for about 30 minutes, then pushed into rocket engine tubes. It goes without saying that you shouldn’t try this one at home unless you’re really sure of what you’re doing!

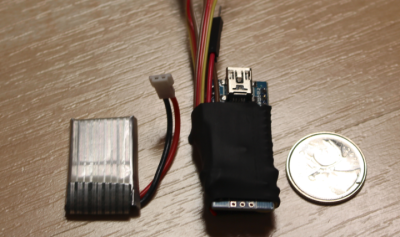

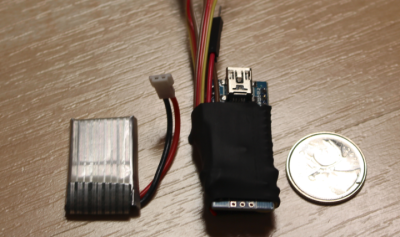

Everyone wants to know how high their rocket went. [Vcazan] created AltiRocket to record acceleration and altitude data. AltiRocket also transmits the data to the ground via a radio link. An Arduino Nano keeps things light. A BMP108 barometric sensor captures pressure data, which is easily converted into altitude. Launch forces are captured by a 3 Axis accelerometer. A tiny LiPo battery provides power. The entire system is only 23 grams! [Vcazan] has already flown AltiRocket, collecting data from several flights earlier this summer.

Everyone wants to know how high their rocket went. [Vcazan] created AltiRocket to record acceleration and altitude data. AltiRocket also transmits the data to the ground via a radio link. An Arduino Nano keeps things light. A BMP108 barometric sensor captures pressure data, which is easily converted into altitude. Launch forces are captured by a 3 Axis accelerometer. A tiny LiPo battery provides power. The entire system is only 23 grams! [Vcazan] has already flown AltiRocket, collecting data from several flights earlier this summer.

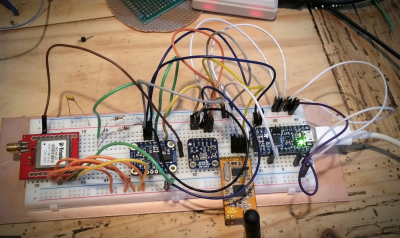

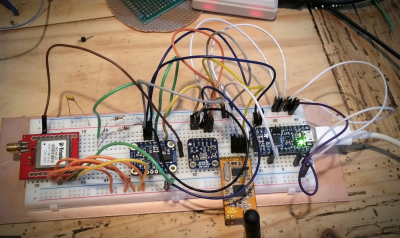

Finally we have [J. M. Hopkins] who is working on a huge project to do just about everything! High Power Experimental Rocket Platform includes designing and building everything from the rocket fuel, to the rocket itself, to a GPS guided parachute recovery system. [J. M. Hopkins] has already accomplished two of his goals, making his own fuel and testing nozzle designs. The electronics package to be included on the rocket is impressive, including a GPS, IMU, barometric, and temperature sensors. Data will be sent back to the ground by a 70cm transceiver. The ground station will use a high gain human-guided yagi tracking antenna with a low noise amplifier to pick up the signal.

Finally we have [J. M. Hopkins] who is working on a huge project to do just about everything! High Power Experimental Rocket Platform includes designing and building everything from the rocket fuel, to the rocket itself, to a GPS guided parachute recovery system. [J. M. Hopkins] has already accomplished two of his goals, making his own fuel and testing nozzle designs. The electronics package to be included on the rocket is impressive, including a GPS, IMU, barometric, and temperature sensors. Data will be sent back to the ground by a 70cm transceiver. The ground station will use a high gain human-guided yagi tracking antenna with a low noise amplifier to pick up the signal.

If you want more rocketry goodness, check out our brand new rocket project list! Rocket projects move fast, if I missed yours as it streaked by, don’t hesitate to drop me a message on Hackaday.io. That’s it for this week’s Hacklet, As always, see you next week. Same hack time, same hack channel, bringing you the best of Hackaday.io!