A disclaimer: Not a single cable tie was harmed in the making of this backpack cyberdeck, and considering that we lost count of the number of USB cables [Bag-Builds] used to connect everything in it, that’s a minor miracle.

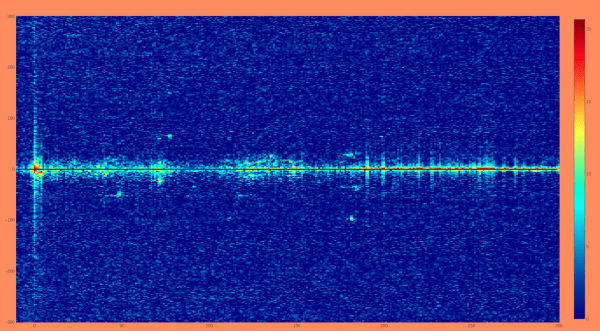

The onboard hardware is substantial, starting with a Lattepanda Sigma SBC, a small WiFi travel router, a Samsung SSD, a pair of seven-port USB hubs, and a quartet of Anker USB battery banks. The software defined radio (SDR) gear includes a HackRF One, an Airspy Mini, a USRP B205mini, and a Nooelec NESDR with an active antenna. There are also three USB WiFi adapters, an AX210 WiFi/Bluetooth combo adapter, a uBlox GPS receiver, and a GPS-disciplined oscillator, both with QFH antennas. There’s also a CatSniffer multi-protocol IoT dongle and a Flipper Zero for good measure, and probably a bunch of other stuff we missed. Phew!

As for mounting all this stuff, [Bag-Builds] went the distance with a nicely designed internal frame system. Much of it is 3D printed, but the basic frame and a few rails are made from aluminum. The real hack here, though, is getting the proper USB cables for each connection. The cable lengths are just right so that nothing needs to get bundled up and cable-tied. The correct selection of adapters is a thing of beauty, too, with very little interference between the cables despite some pretty tightly packed gear.

What exactly you’d do with this cyberpack, other than stay the hell away from airports, police stations, and government buildings, isn’t exactly clear. But it sure seems like you’ve got plenty of options. And yes, we’re aware that this is a commercial product for which no build files are provided, but if you’re sufficiently inspired, we’re sure you could roll your own.

Continue reading “Cyberpack Puts All The Radios Right On Your Back” →