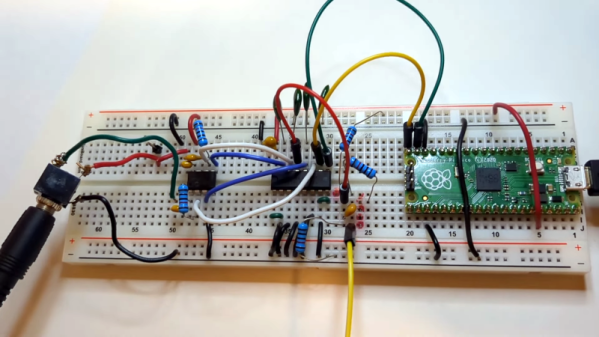

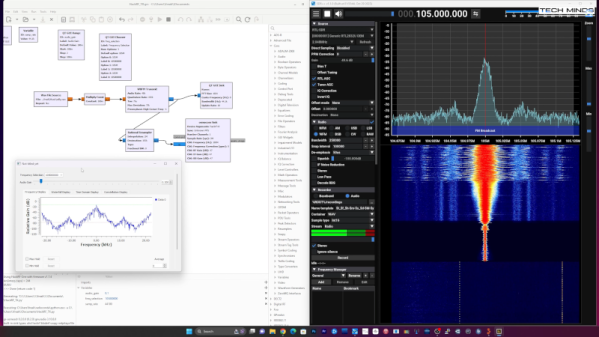

[Grug Huhler] built a simple Tayloe mixer and detector on a breadboard. He decided to extend it a bit to be a full-blown software defined radio (SDR). He then used WSJT-X to monitor FT8 signals and found that he could pick up signals from all over the world with the little breadboard system.

A Raspberry Pi Pico generates a quadrature clock that acts as the local oscillator for the radio. All the processing of the input signal to a quadrature signal is done with a 74LV4052A, which is nothing more than an analog multiplexer. In principle, the device takes a binary number from zero to three and uses it to connect a common signal to one of four channels. There are two common lines and two sets of four channels. In this case, only half of the chip is in use.

An antenna network (two resistors and a capacitor) couples the antenna to one of the common pins, and the Pi generates two square waves, 90 degrees out of phase with each other. This produces select signals in binary of 00, 01, 11, and 10. An op amp and a handful of passive components couple the resulting signals to a PC soundcard, where the software processes the data. The Pi can create clocks up to about 15 or 20 MHz easily using the PIO.

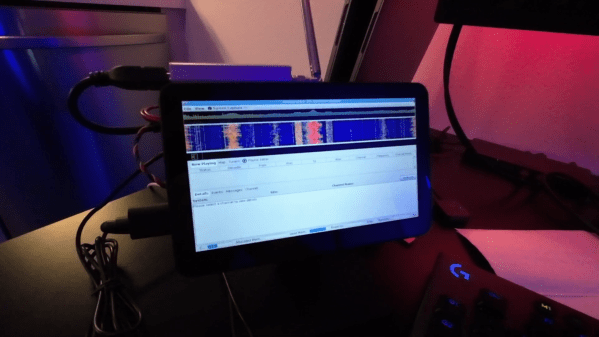

The antenna is a 20-meter-long wire outside, and that accounts for some of the radio’s success. There are several programs than can work with soundcard input like this and [Grug] shows Quisk as a general-purpose receiver. If you missed the first video explaining the Tayloe mixer design, you can catch it below the first video.

This isn’t the first breadboard SDR we’ve seen, but they all use different parts. We’ve even seen a one-bit SDR with three components total (not including the microcontroller). Seriously.