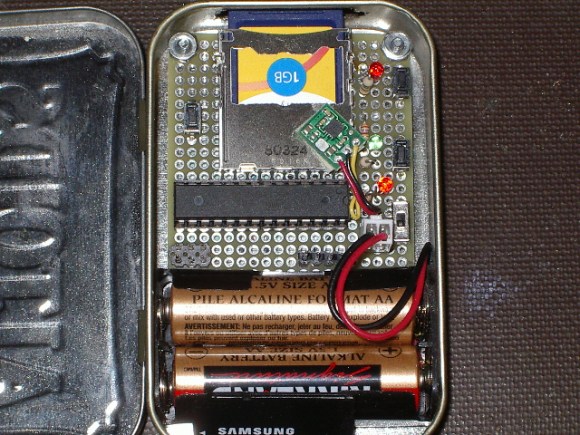

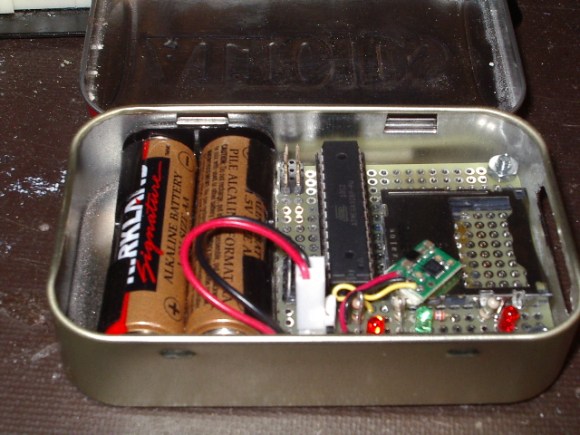

Some of our readers noticed that the Hackaday community open-source offline password keeper (aka Mooltipass) has two incompatible characteristics: being secure and Arduino compatible.

Why is that? Arduino compatibility implies including a way to change the device firmware and accessing the microcontroller’s pins to connect shields. Therefore, some ill-intentioned individuals may replace the original firmware with one that would log all user’s inputs and passwords, or in another case simply sniff the uC’s signals. The ‘hackers’ would then later come to extract the recorded data. Consequently, we needed a secure tamper-proof Mooltipass version and an Arduino-compatible one, while allowing the former to become the latter.

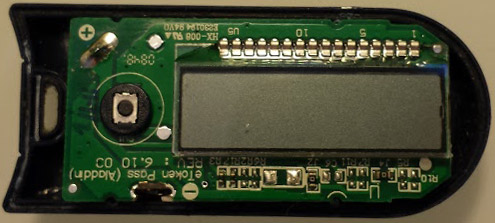

Olivier’s design, though completely closed, will have several thinner surfaces directly above the Arduino headers. As a compromise, we therefore thought of sending a bootloader-free assembled version to the people only interested in the password keeper functionality, while sending a non-assembled version (with a pre-burnt bootloader) to the tinkerers. The Arduino enthusiasts would just need to cut the plastic at the strategic places (and perhaps solder headers to save costs). The main advantage of doing so is that the case would be the same for both versions. The drawback is that each board would have a different firmware depending on who it is intended for.

What do our reader think? For more detailed updates on the Mooltipass current status, you can always join the official Google group.