Although the benefits of semiconductor technology were undeniable during the second half the 20th century, there was a clear divide between the two sides of the Iron Curtain. Whilst the First World had access to top-of-the-line semiconductor foundries and engineers, the Second World was having to get by with scraps. Unable to keep up with the frantic pace of the USA’s developments in particular, the USSR saw itself reduced to copying Western designs and smuggling in machinery where possible. A good example of this is the USSR’s first mass-produced dynamic RAM (DRAM), the 565RU1, as detailed by [The CPUShack Museum].

While the West’s first commercially mass-produced DRAM began in 1970 with the Intel 1103 (1024 x 1) with its three-transistor design, the 565RU1 was developed in 1975, with engineering samples produced until the autumn of 1977. This DRAM chip featured a three-transistor design, with a 4096 x 1 layout and characteristics reminiscent of Western DRAM ICs like the Ti TMS4060. It was produced at a range of microelectronics enterprises in the USSR. These included Angstrem, Mezon (Moldova), Alpha (Latvia) and Exciton (Moscow).

Of course, by the second half of the 1970s the West had already moved on to single-transistor, more efficient DRAM designs. Although the 565RU1 was never known for being that great, it was nevertheless used throughout the USSR and Second World. One example of this is a 1985 article (page 2) by [V. Ye. Beloshevskiy], the Electronics Department Chief of the Belorussian Railroad Computer Center in which the unreliability of the 565RU1 ICs are described, and ways to add redundancy to the (YeS1035) computing systems.

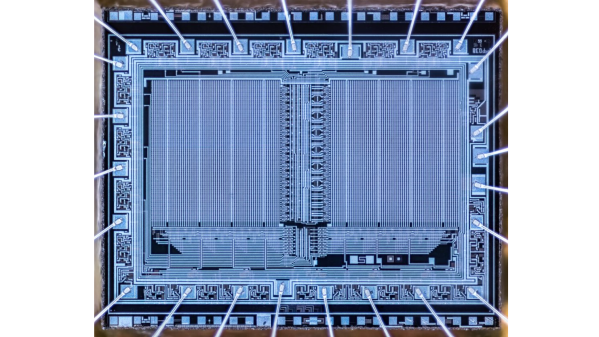

Top image: 565RU1 die manufactured in 1981.