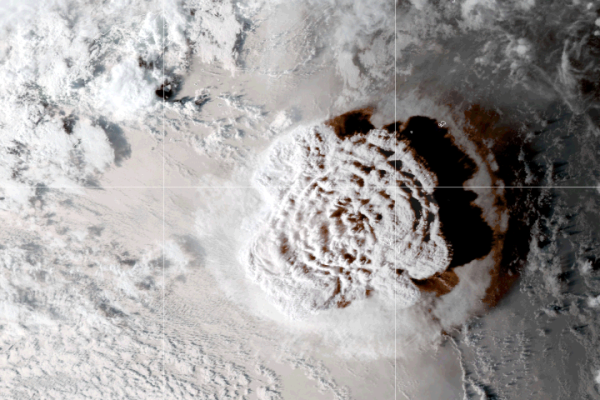

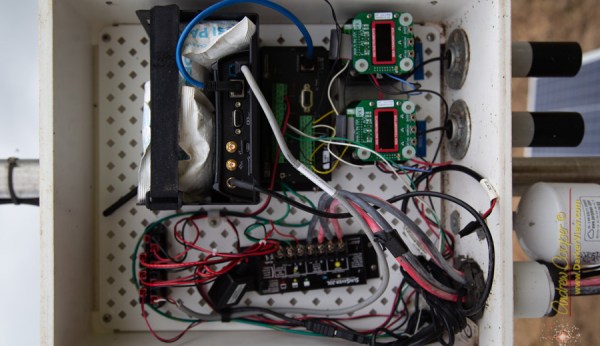

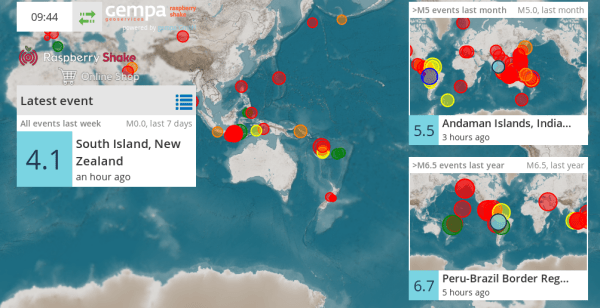

When Tonga’s Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha’apai volcano erupted on January 15, one hacker in the UK knew just what to do. Sandy Macdonald from York quickly cobbled together a Raspberry Pi and a pressure/humidity sensor board and added a little code to create a recording barometer. The idea was to see if the shock wave from the eruption would be detectable over 16,000 km away — and surprise, surprise, it was! It took more than 14 hours to reach Sandy’s impromptu recording station, but the data clearly show a rapid pulse of increasing pressure as the shockwave approached, and a decreased pressure as it passed. What’s more, the shock wave that traveled the “other way” around the planet was detectable too, about seven hours after the first event. In fact, data gathered through the 19th clearly show three full passes of the shockwaves. We just find this fascinating, and applaud Sandy for the presence of mind to throw this together when news of the eruption came out.

Good news for professional astronomers and others with eyes turned skyward — it seems like the ever-expanding Starlink satellite constellation isn’t going to kill ground-based observation. At least that’s the conclusion of a team using the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at the Palomar Observatory outside San Diego. ZTF is designed to catalog anything that blinks, flashes, or explodes in the night sky, making it perfect to detect the streaks from the 1,800-odd Starlink satellites currently in orbit. They analyzed the number of satellite transients captured in ZTF images, and found that fully 20 percent of images show streaks now, as opposed to 0.5 percent back in 2019 when the constellation was much smaller. They conclude that at the 10,000 satellite full build-out, essentially every ZTF image will have a streak in it, but since the artifacts are tiny and well-characterized, they really won’t hinder the science to any appreciable degree.

Speaking of space, we finally have a bit of insight into the causes of space anemia. The 10% to 12% decrease in red blood cells in astronauts during their first ten days in space has been well known since the dawn of the Space Age, but the causes had never really been clear. It was assumed that the anemia was a result of the shifting of fluids in microgravity, but nobody really knew for sure until doing a six-month study on fourteen ISS astronauts. They used exhaled carbon monoxide as a proxy for the destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) — one molecule of CO is liberated for each hemoglobin molecule that’s destroyed — and found that the destruction of RBCs is a primary effect of being in space. Luckily, there appears to be a limit to how many RBCs are lost in space, so the astronauts didn’t suffer from complications of severe anemia while in space. Once they came back to gravity, the anemia reversed, albeit slowly and with up to a year of measurable changes to their blood.

From the “Better Late Than Never” department, we see that this week that Wired finally featured Hackaday Superfriend Sam Zeloof and his homemade integrated circuits. We’re glad to see Sam get coverage — the story was also picked up by Ars Technica — but it’s clear that nobody at either outfit reads Hackaday, since we’ve been featuring Sam since we first heard about his garage fab in 2017. That was back when Sam was still “just” making transistors; since then, we’ve featured some of his lab upgrades, watched him delve into electron beam lithography, and broke the story on his first legit integrated circuit. Along the way, we managed to coax him out to Supercon in 2019 where he gave both a talk and an interview.

And finally, if you’re in the mood for a contest, why not check out WIZNet’s Ethernet HAT contest? The idea is to explore what a Raspberry Pi Pico with Ethernet attached is good for. WIZNet has two flavors of board: one is an Ethernet HAT for the Pico, while the other is as RP2040 with built-in Ethernet. The good news is, if you submit an idea, they’ll send you a board for free. We love it when someone from the Hackaday community wins a contest, so if you enter, be sure to let us know. And hurry — submissions close January 31.