I finally did it. After years of wanting one (and pushing off projects because I didn’t have one) I finally bought an oscilloscope. Over the years I read and watched a ton of content about how to use a scope, you’d think I would know what I’m doing. Turns out that, like anything, hands-on time with an oscilloscope quickly highlighted the gaping holes in my knowledge. And so we begin this recurring column called Scope Noob. Each installment will focus on a different oscilloscope-related topic. This week it’s measuring a test signal and probing Alternating Current.

Measuring a Signal

Hey, measuring signals is what oscilloscopes are all about, right? My very first measurement was, of course, the calibration signal built into the scope. As [Chris Meyer] at Sector67 hackerspace here in Madison put it, you want to make sure you can probe a known signal before venturing into the unknown.

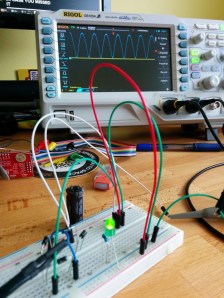

In this case I’m using channel 2. Everything on this scope is color-coded, so the CH2 probe has blue rings on it, the probe jack has a blue channel label, and the trace drawn on the screen is seen in blue. I’m off to a fantastic start!

This scope, a Rigol 1054z, comes with an “auto” button which will detect the signal and adjust the divisions so that the waveform is centered on the display. To me this feels like a shortcut so I made sure to do all of this manually. I started with the “trigger” which is a voltage threshold at which the signal will be displayed on the screen. The menu button brings up options that will let you choose which channel to use as trigger. From there it was just a matter of adjusting the horizontal and vertical resolution and position before using the “cursor” function to measure the wave’s voltage and time.

I played around with the scope a bit more, measuring some PWM signals from a microcontroller. But you want to branch out. Because I don’t have a proper signal generator, the next logical thing to measure is alternating current in my home’s electrical system. I suppose you could call it a built-in sine wave source.

Probing Alternating Current

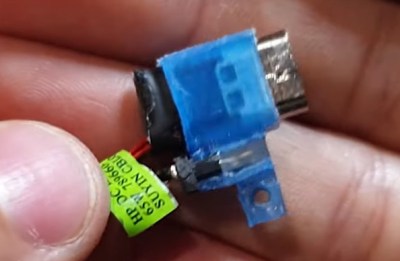

I sometimes take criticism for never throwing things away. Seven years ago we had a cat water fountain whose motor seized. It was powered by a 12V AC to AC converter seen here. Yep, I kept it and was somehow able to find it again for this project.

Of course at the time I thought I would build a clock that measures mains frequency to keep accurate time. This would have done the trick had I followed through. But for now I’m using it to protect me (and my fancy new scope) from accidental shock. I’ll still get the sine wave I’m looking for but with a source that is only 12V at 200 milliamps.

Don’t measure mains directly unless you have a good reason to do so.

Continuing on my adventure I plugged in the wall wart and connected the probe to one of the two wires coming out of it. But wait, what do I do with the probe’s reference clip? I know enough about home electrical to know that one prong of the plug is hot, the other is neutral. The clip itself is basically connected directly to mains ground. Bringing the two together sounds like a really bad idea.

This turns out to be a special case for oscilloscopes, and one that prompted me to think about writing this column. Had this been a 3-prong wall wart, connecting the probe’s reference clip to one of the wires would have been a very bad thing. Many 3-prong wall warts reference the mains earth ground on one of the outputs. If that were the case you could simply leave the clip unconnected as the chassis ground of your scope is already connected to mains ground via its own 3-prong power cord and the reference clip is a dead short to that. If you did need to probe AC using the reference clip you need an isolation transformer for your scope. There are bigger implications when probing a board powered from mains which [Dave Jones] does an excellent job of explaining. Make sure you check out his aptly named video: How NOT to blow up your oscilloscope.

As I understand it, and I hope you’ll weigh in with a comment below, since the wall wart I’m using has a transformer and no ground plug I’m fine using the ground clip of the probe in this case. Even though I’m clipping it to an AC line, the transformer prevents any kind of short between hot/neutral mains and earth ground (via the probe’s ground clip). What I don’t understand is why it’s okay to connect the transformed side of the 12V AC to mains ground?

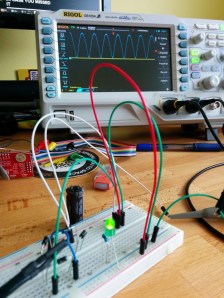

At any rate, the screenshots above show my progress through this measurement. I first connected the probe without the ground clip and got the sad-looking trace seen on the left. After conferring with both [Adam Fabio] and [Bil Herd] (who had differing opinions on whether or not I should “float the scope”) I connected the ground clip and was greeted with a beautifully formed sine wave. I’m calling this a success and putting a notch in the old bench to remember it by.

What’s Next?

I don’t want to get too crazy with the first installment of Scope Noob so I’ll be ending here for now. I need your guidance for future installments. What interesting quirks of an oscilloscope should a noob like me explore? What are your own questions about scope use? Leave those below and we’ll try to add them to the lineup in the coming weeks.

I don’t want to get too crazy with the first installment of Scope Noob so I’ll be ending here for now. I need your guidance for future installments. What interesting quirks of an oscilloscope should a noob like me explore? What are your own questions about scope use? Leave those below and we’ll try to add them to the lineup in the coming weeks.

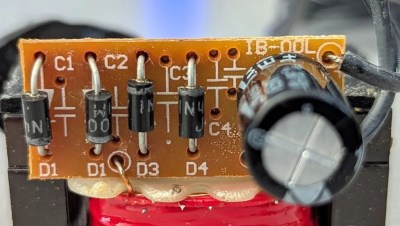

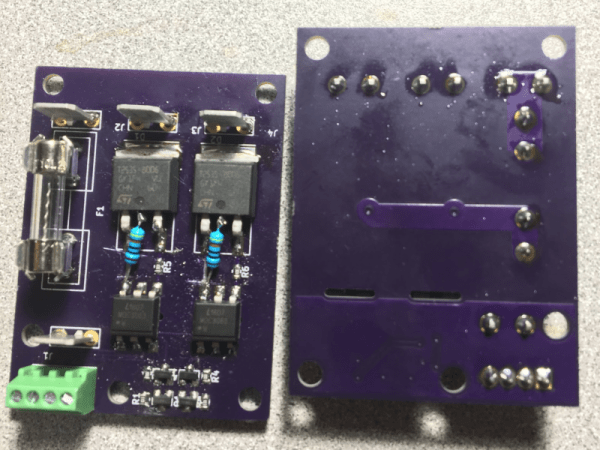

Homework

For next week I’m working my way through the adventure of rectifying this 12V AC signal into a smoothed DC source. Here you see a teaser of those experiments. I’ve built a full-wave rectifier using just four diodes (1N4001) and will plunk in a hugely-over-spec’d electrolytic capacitor to do the smoothing. If you want to follow along on the adventure you should dig around your parts drawers for these components and give it a try yourself this week. We’ll compare notes in the next post!

I don’t want to get too crazy with the first installment of Scope Noob so I’ll be ending here for now. I need your guidance for future installments. What interesting quirks of an oscilloscope should a noob like me explore? What are your own questions about scope use? Leave those below and we’ll try to add them to the lineup in the coming weeks.

I don’t want to get too crazy with the first installment of Scope Noob so I’ll be ending here for now. I need your guidance for future installments. What interesting quirks of an oscilloscope should a noob like me explore? What are your own questions about scope use? Leave those below and we’ll try to add them to the lineup in the coming weeks.