Most hobbies come with a lot of tools, and thread injecting is no different. Quilting itself may be Queen Hobby when it comes to the sheer volume of things you can buy: specialized templates, clips, thimbles, disappearing ink pens, and so on. And of course, you want it all within arm’s reach while sitting at the machine.

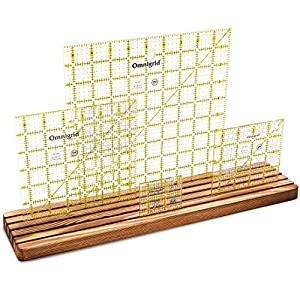

Years ago, [KevsWoodworks] built an impressive custom quilting desk for his wife. He’d added on to it over the years, but it was time for a bigger one. This beautiful beast has 21 drawers and 6 large cubbyholes for plastic bins. At the wife’s request, one of the drawers is vertical. [Kev] doesn’t say what she put in there, but if it were our desk, that’s where we’d stash all our large plastic rulers that need to be kept flat (or vertical). There’s also a lift, so any sewing machine can be brought up flush with the enormous top.

Fortunately for us, [Kev] likes to teach. He documented the build in a series of videos that go nicely with his CAD drawings, which are available for download. Thread your way past the break to see those videos.

Want to do some thread injecting, but don’t want to spend hundreds on a machine? We got lucky with our entry-level injector. If yours is a piece of scrap or has limited stitch options, replace the motor, or add an Arduino.