The current state of the art of embedded motion sensing is based around micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) devices. These miracles of microfabrication use tiny silicon structures, configured to detect acceleration and rotational velocity in three dimensions. Accumulate these accelerations and rotations, and you’ve got a device that can find its orientation and track movement without any external waypoints. This is the basis of the technique of dead reckoning.

Why do we care about dead reckoning anyway? Surely GPS and related positioning systems are good enough? Above ground GPS is usually good enough, but underwater and underground this simply won’t work. Even heading indoors has a dramatic effect on the GPS signal strength, so yes, we need another way for some applications.

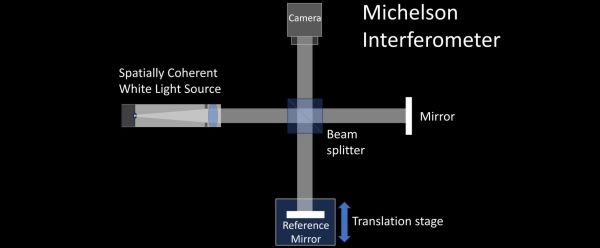

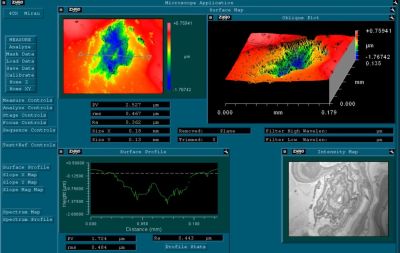

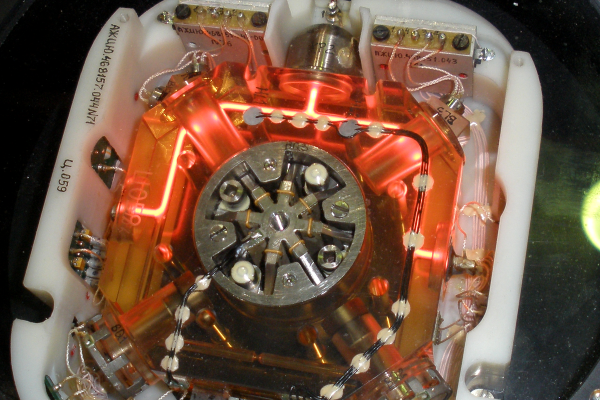

Right now, the current state of the art in portable sensors are MEMS devices, and you can get them for the cost of a hamburger. But if you want the ultimate in accuracy, you’ll want a quantum atomic interferometer. What that is, and how it will be possible to make one small enough to be useful, is half of the story. But first, let’s talk MEMS.

Continue reading “Quantum Atomic Interferometer For Precision Motion Sensing”